Parchment Part 1

Parchment: Medieval Availability & Use

|

| Deerskin parchment, with a duck feather quill pen. |

In the medieval period, scribes across Europe relied upon animal skin for their painting/writing/book-making medium. Paper existed (such as papyrus, in northern Africa, hemp and mulberry paper in Asia) but in the colder, wetter climate of northern Europe, animal skin was comparatively abundant, affordable, more durable and easier to make. Skins were a constant natural byproduct of butchering livestock for meat. Flat, stretched rawhide, called parchment or vellum (depending on thinness & quality), could be written upon with char pencil, chalk, ink or paint; it could be dyed special colors and cut into useful shapes (rectangles, hearts, etc), and it would last for centuries, so long as it was kept dry. It was also far more reusable than papyrus.

Cow, goat, sheep and deer skin could all be made into parchment without too much labor investment, and the skin from the young animals (calf, kid and lamb) was thin and fine enough to make vellum, for books or important legal documents. High-quality vellum was white or ivory in color, evenly thin and flexible, and unblemished. However, a plain rawhide skin with the hair removed, stretched tightly while drying, and sanded, would serve as regular parchment for everyday purposes (even with holes in it or discolorations or uneven sides).

Parchment might be used repeatedly, since the ink did not penetrate all the way through the skin and thus could be scraped off with a knife; thus creating palimpsests in some medieval books that still exist today. The word palimpsest actually means 'scraped clean,' referring to the most common way of reusing parchment. A loose sheet of parchment could also be washed, then restretched, if a cleaner page was needed.

The edge trimmings and scraps left over from making rectangular sheets of parchment could be used to scribble down messages, test ink, practice calligraphy, or sketch. The unusable parts of the hide, cut away after stretching, could be boiled down to create hide glue. Rawhide that was too thin, fragile or full of holes could still serve other functions, such as screens for lanterns, small rawhide boxes, or even stretched and plied rawhide cord.

|

| Edge trimmings from cutting rectangular sheets can still be useful as parchment scraps or for making hide glue. |

For perspective on its value, consider that parchment was rawhide, and thus required far less time (a few days, rather than months) and input (potentially no added chemicals at all, or else just lye or slaked lime), compared with vegetable-tanned leather. Leather was plentiful in the medieval period of northern Europe, and was, in turn, less labor-intensive to make than was fabric. Thus, cloth was more precious than leather, which in turn was more precious than parchment.

For example, in the mid-1300's in England, good quality wool cloth cost 5 shillings* per yard, low quality wool cost 1 shilling per yard, plain linen cost 1 shilling per yard, and leather shoes cost 6 pence (half a shilling). A live wether (a castrated male sheep for butchering, which would provide fleece, skin, meat, bones, tallow and glue) cost about a shilling (1). Labor had its price, as well. In 1300, England established the wage for the tawing of fur hides at 0.06 pence per squirrel skin (2). Tawing fur requires both greater labor and more chemical input (alum, cream of tartar and oil) than making parchment, so we can surmise that the relative worth of a parchmenter's time was less (although finding specifics on that is difficult, since many monasteries made their own parchment and thus did not pay wages for that labor). It is worth noting that after the Black Plague, the cost of labor increased dramatically, thus driving up the cost for parchment. Still, even with higher prices, in the fifteenth century, the cost for the parchment to make MS Peterhouse 110, consisting of 27 quires or 216 sheets of parchment, was 6 shillings and 9 pence, or 0.375 pence per sheet (3). For reference, a dozen eggs cost one penny, and tallow candles cost 1.5 pence per pound (1).

All of this is not to say that parchment was cheap, but rather to give perspective on its relative worth and dispel the common myth that it was prohibitively expensive for the medieval middle-class to buy or use parchment. The real expense in buying a book or manuscript lay not in the material, but in the scribe's labor. Between 74% to 80% of the cost of a medieval book came from the scribal and book-binding labor involved in making it, and only a quarter of the cost came from the materials (skin, glue, ink, pigments, etc) (3).

|

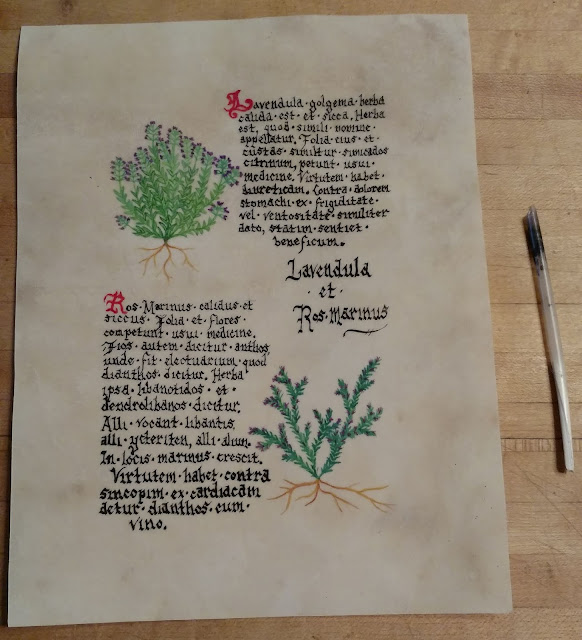

| Calligraphy and illumination comprised the main value of a manuscript because these were time-consuming, specialized, scholarly skills. |

*Shillings and pence: a shilling = 12 pence (pennies)

Sources

1. Hodges, Kenneth. "List of price of medieval items." <http://medieval.ucdavis.edu/120D/Money.html> A survey of sources studying prices in the 13th-15th centuries, especially referencing Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages. Dyer, Christopher. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

2. Veale, Elspeth M, 'III. "The Emergence of the London Skinners." The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages, Vol. 38, pp. 36-56. London, 2003.

3. Overty, Joanne. "The Cost of Doing Scribal Business: Prices of Manuscript Books in England, 1300-1483.” Book History, Vol. 11, p. 1-32. John Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions and suggestions for further research are welcome. No selling, no trolling, and back up any critique with modern scholarly sources. Comments that do not meet these criteria will be discarded.