Lye Part 4

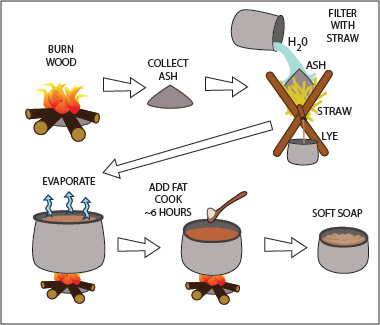

Lye Part 4: Saponification To read the first post about the history of lye, see: Lye Part 1 . To read about potash lye, see Lye Part 2 , and for soda ash lye, see Lye Part 3 . Saponification Saponification is the chemical reaction between an alkaline substance and a fatty acid, making soap. Alkaline detergents can be very harsh and corrosive. Saponification lessens their cleansing ability to some extent, but it also makes them safer to use. A strong lye can burn the skin from brief contact, and even a weak lye will dry and irritate the hands in the time it takes to wash a bunch of laundry or dishes. Soap preserves enough cleansing power to aid in washing, but it is mild and unlikely to bother any but the most sensitive skins. In some cases, extra fat is added to soap so that is soothing or moisturizing—a far cry from the lye that made it. Chemistry of Saponification Saponification is a form of hydrolysis (1) . Fatty acids consist of long chains of hydrocarbons (CH2), someti