Parchment Part 2

Parchment: an Overview of the Material

Definition

Parchment is the cleaned, stretched skin of an animal, untanned, that is used as a writing medium. In medieval Europe it was the most common carrier for calligraphy or illuminations, whether bound into a book or left as a loose sheet or wrapped around a wooden dowel as a scroll.

Skin sources

Not all hides serve equally for making parchment. Pig skin, for example, has large, coarse pores, and the hair follicles go all the way through the hide. A parchment made from pig skin would have tiny holes everywhere, and a rough texture that would quickly dull the scribe's quill. Pig skin is also extremely thick/heavy, which would make very stiff, bulky parchment; it would not do well for making thin, flexible sheets for bookbinding. Horse, and other thick-skinned animals, would likewise make very stiff and coarse parchment (unless the parchmenter was able to split the hide into two sheets, but this is a relatively advanced skill and adds to the time/labor involved). Nonetheless, virtually every type of skin has probably been made into parchment at some point in medieval history--from fish to human and every available animal in between!

Cow, goat and sheep (and other ruminants, like deer) made up most of the parchment hides in the medieval period. Ruminants tend to have close-grained, smooth textures and relatively fine skins, which is why they were preferred for parchment. The younger the animal, the finer the skin and the thinner the parchment that could be made from it. Vellum, so named because it often came from 'veal' skins, made the thinnest and finest large sheets of parchment. Even the skin of a miscarried livestock baby (fetal calf or kid or lamb) might be saved and turned into a valuable sheet of super-thin vellum (thus salvaging some good from what was otherwise a tragic waste). Of course, the smaller the hide, the smaller the resulting sheets of parchment that could be made from it. Trying to make too large of a sheet from too small a hide results in wrinkles.

Skin layers

Skin (the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis--or, the cutis and the subcutis) forms in layers on top of the flesh of an animal. These layers, though all built of a matrix of collagen, fibers, fats and proteins, each have different properties.

Grain: The outer layer, where the epidermis meets the dermis, is often called the "grain" in leather working. This is where the pigment of a skin resides, and often includes the scales and hair follicles (although follicles may reach deeper layers of the skin, depending on the species). The grain is often removed for tanning, buck-skinning and parchment making, since this layer can dry differently than the inner dermal layer and cause stiffening or uneven shrinkage.

Corium: The central layer, the dermis, makes up the main part of any animal hide, leather, parchment or buckskin. It may include hair follicles and veins, as well as possible pigmentation, but this layer is often solid, free of veins, and white.

Flesh: The inner layer, the subcutis, includes most of the veins and 'twitchy' muscles connected to an animal's skin, as well as much of the fat of the hide. This layer MUST be removed for a hide to be kept, for these are the elements that are most prone to rot and insect damage. Salting or freezing may preserve a skin with the flesh layer on, but humidity or thawing will cause the skin to decay.

Skinning: With a sharp knife, sometimes a blunt-tipped or rounded knife, the hide is slit up the belly and around the ankles of the dead animal. The skin may pull free easily at this point, but with most animals the process involves pulling, then cutting connective membrane, then pulling, to cleanly take the skin without pulling off meat. The more flesh left with the carcass, and not on the skin, the better for butchery and the easier the next step with the skin will be.

Fleshing: This follows the initial removal of the skin from the animal, but need not happen immediately. If the skinner is also the butcher, it may be important to continue working on the meat of the carcass. In that case, the hide can be put in clean, cold water to soak, or spread out well and dried with salt. Soaking or salting the hide loosen some of the connective tissue, making the scraping process easier. Fleshing involves scraping the remaining muscles, tendons, veins and membrane of connective tissue off the inner side of the hide. The hide is usually scraped wet, although there are dry-scrape techniques. Wet scraping requires a smooth, flat implement with a dull blade area and a way to grip it well—ideally on both sides of the scraper—and a smooth, round surface over which to lay the hide, fur-down.

A scraping beam can be made of wood, or stone, or modernly a PVC pipe. The narrower the beam, the more pressure the scraper will apply in each individual location, but the less area will be scraped moment-to-moment. The wider the beam, the more contact the scraper makes and the more area it scrapes, but the less force it applies to one spot. A happy medium diameter is usually between 4” to 8” for most types of hide, although a wider beam will work if the parchmenter normally works easy hides.

After fleshing, the hide can be rinsed and put into the alkaline bath.

Bucking: Also called liming, because this stage involves soaking the hide in a strong alkaline solution which is usually made with hydrated lime. The strong base swells the pores of the hide, loosening the tissue of skin and making the hair release from its follicles. Depending on temperature (hot weather accelerates the process) and strength of the bath (it will be moderately dangerous to touch with bare hands) and the thickness of the hide, this soak can take anywhere from a couple of days to several weeks. The hide should be stirred periodically, to ensure even exposure to the chemical. When a gentle tug makes the fur slip out easily, the skin is ready. Waiting too long will permanently weaken the hide.

When the hide is swollen, it will be rubbery and slimy to the touch. The hairs will be loose and the outer layer of epidermis will scrape off easily. The parchmenter should return the hide to the scraping beam, this time with the fur up. Beginning in the middle, the parchmenter will scrape away hair and pigment and the outer layer of follicles, working outward to the edges of the hide.

Once the hide is bare on both sides, it can be rinsed and neutralized, or it can be grained.

Graining: More accurately called "de-graining" or removing the grain, this step helps soften and thin the skin for making parchment. It is not absolutely necessary, but if done it improves the quality of the finished product. Graining can be done immediately after removing the fur, if the outer layer of skin is ready to peel off, or it may require another soak in the lime bath.

Graining is similar in process to the prior two steps, only with more pressure, as the scraper now needs to penetrate a layer of the skin and peel it away. Once an area it started, this becomes easier, since the grain can be rolled away in a layer with the scraper. However, this is still a challenging step and remnant scraps of grain may be left at the end. These can be sanded off in the finishing stages.

Now the hide should be rinsed in multiple water baths to leach the alkali out of it, or even neutralized with a weak vinegar solution to speed the process, until the rubbery sliminess has left the hide and the pores have returned to normal.

Stretching: The skin must be completely soaked, or stretching it will cause rips. After soaking, the hide can be wrung out to remove excess moisture from the surface. Then, slits are poked along the edges and strings run from the slits to a stretching frame. The frame has to be larger than the hide; if the hide is too big, it may need to be trimmed or divided into multiple pieces. If dividing a hide, cut it into quarters, starting along the spine, since stretching across a spine is one of the challenges of this stage. However, the parchmenter will get more finished product if the whole hide can be worked on one frame. The wet hide is pulled taut, like the cover of a drum. Then, using a curved implement like a round cheese knife, a scapula (shoulder blade) or a specialized knife called a lunella, the parchmenter scrapes the flesh side of the hide again, working deeply as the hide stretches out away from the frame. This work demands strength and stamina. The whole hide must be worked until it has dried, with the stretchy slack being taken up by regular tightening of all of the strings. No pouching or slack should be left at the end, as the hide dries flat and white. Any areas that remain clear, or stiffen badly, did not stretch sufficiently.

Re-wetting can help with timing, if the weather dries the hide before the parchmenter can finish stretching it. Applying water to the drying patches while working will keep the hide moist. If it dries out too much, the whole hide can be taken down and resoaked in a water bath; rawhide absorbs water much more slowly than wet skin, so applying handfuls of water to the surface may not suffice once the hide has dried too far to be as absorbent.

Once stretched, a hide is easier to stretch again, or stretch further, so it is legitimate to stretch the hide until it is dry, and then soak it and stretch it again later. This particularly helps if scraps of grain were left on the hide and cause uneven stretching and drying. Once dry, the hide can be sanded to remove those grain spots. Then it can be soaked and stretched evenly.

Sanding: Using pumice, or parchmenter's bread (a loaf baked with powdered pumice in the dough), or modern sandpaper, the dry, flat, stretched hide is buffed while still on the stretching frame. The powdered skin removed by this process is not safe to inhale, so wearing a mask is advisable. The goal of sanding is to scratch the flat layers of dried skin to raise a nap, and buff that nap into a finer and finer fuzz until the surface is soft, smooth and absorbent. This allows ink and paint to bind onto the surface, where otherwise they might bead up or flake off, but care should be taken to sand finely enough that no coarse fuzz will clog the calligraphy nibs, or bumps impede the painting.

Cutting: After sanding, the parchment is ready to be measured out into rectangles (or other shapes) for book pages, loose sheets, or scrolls. It can be cut on a cutting board, or using scissors; it behaves like paper. Thoughtful layout of sheets will take into account the spine and any holes in the hide, which can be left in, or avoided, depending on the quality needed for the finished product and the willingness to sacrifice any amount of parchment. Scraps make excellent tags, note cards, labels and practice pieces (for testing inks and paints), or they can be cooked down into hide glue.

Collagen (especially after being treated with alkali or acid baths) is water-soluble, especially in warm water. This is why hide glue can be made by simply simmering scraps of rawhide in water, collecting the "glue liquor," and drying it for later use. Essentially, the sheet that the parchmenter has created by scraping away the inner and outer layers of skin is a panel of hide glue, embedded with the fibers that make up an animal's pores.

A soaked hide, prepared this way, is therefore soft, stretchy (like a rubbery cloth) and moderately sticky (it can be laid upon dry wood or glass and will lightly adhere to the surface). As it dries, however, the collagen (hide glue) sets and becomes rigid, anchoring itself around the fibers and locking in place. A wet hide, left to dry, will become stiff as a board. This is how rawhide boxes are made. The dry hide will no longer stretch; it can even be ripped by hand, like paper, if it is thin enough.

Side note: Buckskinning (brain-tanning or oil-smoke-tanning, as practiced by primitives and survivalists) requires stretching, working and rearranging the hide as it dries, deliberately breaking the collagen protein strands as they set, while they are still damp and flexible. If this process is done properly, the dried hide will be soft and pliable, flexible like fabric. If it is not done thoroughly, some parts will remain stiff or even rigid. If it is attempted when the hide is too dry, it will simply rip. This is a labor-intensive process, but it results in a rawhide that behaves like soft cloth. It can then be preserved by impregnating it with emulsified fats (oil, egg yolks, fermented brain, etc). This soft, oiled hide can then be smoked--the smoke will chemically react with the fats and actually tan the hide, making it safe to wear in the rain or high humidity.

A plain, fleshed hide that is allowed to dry flat will be hard and smooth to the touch. With the fur removed, one can see that the dry, hard hide is translucent (or nearly transparent, if it is very thin). This is how rawhide lantern screens are made. The fibers making the pores of the skin still run from the outer side to the inner side in a relatively straight direction, allowing light to pass through the hide just as perspiration once passed through the skin of the living animal. Furthermore, the hard surface will not accept ink well (it is like writing on smooth wood), so this rigid, translucent material is not ideal for writing. It behaves rather like plastic; rigid, and not readily absorbent.

In order to make the skin turn white and accept ink, the wet skin must be stretched under extreme tension while it dries. This tension pulls the fibers of the pores sideways, making them lay down horizontally, while the collagen is still wet and flexible. As the skin dries out, the collagen dries and locks the pores in place in their new orientation. Thus, the stretched hide becomes opaque and white--but any area that does not get thoroughly stretched flat, while it dries, will end up translucent instead of white. Sometimes a thin skin may require a second stretching, or a rewetting and extra tightening of the tension, in order to get all of the translucent spots to stretch out and become white.

Parchment is the cleaned, stretched skin of an animal, untanned, that is used as a writing medium. In medieval Europe it was the most common carrier for calligraphy or illuminations, whether bound into a book or left as a loose sheet or wrapped around a wooden dowel as a scroll.

Skin sources

Not all hides serve equally for making parchment. Pig skin, for example, has large, coarse pores, and the hair follicles go all the way through the hide. A parchment made from pig skin would have tiny holes everywhere, and a rough texture that would quickly dull the scribe's quill. Pig skin is also extremely thick/heavy, which would make very stiff, bulky parchment; it would not do well for making thin, flexible sheets for bookbinding. Horse, and other thick-skinned animals, would likewise make very stiff and coarse parchment (unless the parchmenter was able to split the hide into two sheets, but this is a relatively advanced skill and adds to the time/labor involved). Nonetheless, virtually every type of skin has probably been made into parchment at some point in medieval history--from fish to human and every available animal in between!

Cow, goat and sheep (and other ruminants, like deer) made up most of the parchment hides in the medieval period. Ruminants tend to have close-grained, smooth textures and relatively fine skins, which is why they were preferred for parchment. The younger the animal, the finer the skin and the thinner the parchment that could be made from it. Vellum, so named because it often came from 'veal' skins, made the thinnest and finest large sheets of parchment. Even the skin of a miscarried livestock baby (fetal calf or kid or lamb) might be saved and turned into a valuable sheet of super-thin vellum (thus salvaging some good from what was otherwise a tragic waste). Of course, the smaller the hide, the smaller the resulting sheets of parchment that could be made from it. Trying to make too large of a sheet from too small a hide results in wrinkles.

Skin layers

Skin (the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis--or, the cutis and the subcutis) forms in layers on top of the flesh of an animal. These layers, though all built of a matrix of collagen, fibers, fats and proteins, each have different properties.

Grain: The outer layer, where the epidermis meets the dermis, is often called the "grain" in leather working. This is where the pigment of a skin resides, and often includes the scales and hair follicles (although follicles may reach deeper layers of the skin, depending on the species). The grain is often removed for tanning, buck-skinning and parchment making, since this layer can dry differently than the inner dermal layer and cause stiffening or uneven shrinkage.

Corium: The central layer, the dermis, makes up the main part of any animal hide, leather, parchment or buckskin. It may include hair follicles and veins, as well as possible pigmentation, but this layer is often solid, free of veins, and white.

Flesh: The inner layer, the subcutis, includes most of the veins and 'twitchy' muscles connected to an animal's skin, as well as much of the fat of the hide. This layer MUST be removed for a hide to be kept, for these are the elements that are most prone to rot and insect damage. Salting or freezing may preserve a skin with the flesh layer on, but humidity or thawing will cause the skin to decay.

Steps in making parchment

Skinning: With a sharp knife, sometimes a blunt-tipped or rounded knife, the hide is slit up the belly and around the ankles of the dead animal. The skin may pull free easily at this point, but with most animals the process involves pulling, then cutting connective membrane, then pulling, to cleanly take the skin without pulling off meat. The more flesh left with the carcass, and not on the skin, the better for butchery and the easier the next step with the skin will be.

Fleshing: This follows the initial removal of the skin from the animal, but need not happen immediately. If the skinner is also the butcher, it may be important to continue working on the meat of the carcass. In that case, the hide can be put in clean, cold water to soak, or spread out well and dried with salt. Soaking or salting the hide loosen some of the connective tissue, making the scraping process easier. Fleshing involves scraping the remaining muscles, tendons, veins and membrane of connective tissue off the inner side of the hide. The hide is usually scraped wet, although there are dry-scrape techniques. Wet scraping requires a smooth, flat implement with a dull blade area and a way to grip it well—ideally on both sides of the scraper—and a smooth, round surface over which to lay the hide, fur-down.

A scraping beam can be made of wood, or stone, or modernly a PVC pipe. The narrower the beam, the more pressure the scraper will apply in each individual location, but the less area will be scraped moment-to-moment. The wider the beam, the more contact the scraper makes and the more area it scrapes, but the less force it applies to one spot. A happy medium diameter is usually between 4” to 8” for most types of hide, although a wider beam will work if the parchmenter normally works easy hides.

After fleshing, the hide can be rinsed and put into the alkaline bath.

Bucking: Also called liming, because this stage involves soaking the hide in a strong alkaline solution which is usually made with hydrated lime. The strong base swells the pores of the hide, loosening the tissue of skin and making the hair release from its follicles. Depending on temperature (hot weather accelerates the process) and strength of the bath (it will be moderately dangerous to touch with bare hands) and the thickness of the hide, this soak can take anywhere from a couple of days to several weeks. The hide should be stirred periodically, to ensure even exposure to the chemical. When a gentle tug makes the fur slip out easily, the skin is ready. Waiting too long will permanently weaken the hide.

When the hide is swollen, it will be rubbery and slimy to the touch. The hairs will be loose and the outer layer of epidermis will scrape off easily. The parchmenter should return the hide to the scraping beam, this time with the fur up. Beginning in the middle, the parchmenter will scrape away hair and pigment and the outer layer of follicles, working outward to the edges of the hide.

Once the hide is bare on both sides, it can be rinsed and neutralized, or it can be grained.

Graining: More accurately called "de-graining" or removing the grain, this step helps soften and thin the skin for making parchment. It is not absolutely necessary, but if done it improves the quality of the finished product. Graining can be done immediately after removing the fur, if the outer layer of skin is ready to peel off, or it may require another soak in the lime bath.

Graining is similar in process to the prior two steps, only with more pressure, as the scraper now needs to penetrate a layer of the skin and peel it away. Once an area it started, this becomes easier, since the grain can be rolled away in a layer with the scraper. However, this is still a challenging step and remnant scraps of grain may be left at the end. These can be sanded off in the finishing stages.

Now the hide should be rinsed in multiple water baths to leach the alkali out of it, or even neutralized with a weak vinegar solution to speed the process, until the rubbery sliminess has left the hide and the pores have returned to normal.

Stretching: The skin must be completely soaked, or stretching it will cause rips. After soaking, the hide can be wrung out to remove excess moisture from the surface. Then, slits are poked along the edges and strings run from the slits to a stretching frame. The frame has to be larger than the hide; if the hide is too big, it may need to be trimmed or divided into multiple pieces. If dividing a hide, cut it into quarters, starting along the spine, since stretching across a spine is one of the challenges of this stage. However, the parchmenter will get more finished product if the whole hide can be worked on one frame. The wet hide is pulled taut, like the cover of a drum. Then, using a curved implement like a round cheese knife, a scapula (shoulder blade) or a specialized knife called a lunella, the parchmenter scrapes the flesh side of the hide again, working deeply as the hide stretches out away from the frame. This work demands strength and stamina. The whole hide must be worked until it has dried, with the stretchy slack being taken up by regular tightening of all of the strings. No pouching or slack should be left at the end, as the hide dries flat and white. Any areas that remain clear, or stiffen badly, did not stretch sufficiently.

Re-wetting can help with timing, if the weather dries the hide before the parchmenter can finish stretching it. Applying water to the drying patches while working will keep the hide moist. If it dries out too much, the whole hide can be taken down and resoaked in a water bath; rawhide absorbs water much more slowly than wet skin, so applying handfuls of water to the surface may not suffice once the hide has dried too far to be as absorbent.

Once stretched, a hide is easier to stretch again, or stretch further, so it is legitimate to stretch the hide until it is dry, and then soak it and stretch it again later. This particularly helps if scraps of grain were left on the hide and cause uneven stretching and drying. Once dry, the hide can be sanded to remove those grain spots. Then it can be soaked and stretched evenly.

Sanding: Using pumice, or parchmenter's bread (a loaf baked with powdered pumice in the dough), or modern sandpaper, the dry, flat, stretched hide is buffed while still on the stretching frame. The powdered skin removed by this process is not safe to inhale, so wearing a mask is advisable. The goal of sanding is to scratch the flat layers of dried skin to raise a nap, and buff that nap into a finer and finer fuzz until the surface is soft, smooth and absorbent. This allows ink and paint to bind onto the surface, where otherwise they might bead up or flake off, but care should be taken to sand finely enough that no coarse fuzz will clog the calligraphy nibs, or bumps impede the painting.

Cutting: After sanding, the parchment is ready to be measured out into rectangles (or other shapes) for book pages, loose sheets, or scrolls. It can be cut on a cutting board, or using scissors; it behaves like paper. Thoughtful layout of sheets will take into account the spine and any holes in the hide, which can be left in, or avoided, depending on the quality needed for the finished product and the willingness to sacrifice any amount of parchment. Scraps make excellent tags, note cards, labels and practice pieces (for testing inks and paints), or they can be cooked down into hide glue.

Additional Notes

Mechanics of stretchingCollagen (especially after being treated with alkali or acid baths) is water-soluble, especially in warm water. This is why hide glue can be made by simply simmering scraps of rawhide in water, collecting the "glue liquor," and drying it for later use. Essentially, the sheet that the parchmenter has created by scraping away the inner and outer layers of skin is a panel of hide glue, embedded with the fibers that make up an animal's pores.

A soaked hide, prepared this way, is therefore soft, stretchy (like a rubbery cloth) and moderately sticky (it can be laid upon dry wood or glass and will lightly adhere to the surface). As it dries, however, the collagen (hide glue) sets and becomes rigid, anchoring itself around the fibers and locking in place. A wet hide, left to dry, will become stiff as a board. This is how rawhide boxes are made. The dry hide will no longer stretch; it can even be ripped by hand, like paper, if it is thin enough.

Side note: Buckskinning (brain-tanning or oil-smoke-tanning, as practiced by primitives and survivalists) requires stretching, working and rearranging the hide as it dries, deliberately breaking the collagen protein strands as they set, while they are still damp and flexible. If this process is done properly, the dried hide will be soft and pliable, flexible like fabric. If it is not done thoroughly, some parts will remain stiff or even rigid. If it is attempted when the hide is too dry, it will simply rip. This is a labor-intensive process, but it results in a rawhide that behaves like soft cloth. It can then be preserved by impregnating it with emulsified fats (oil, egg yolks, fermented brain, etc). This soft, oiled hide can then be smoked--the smoke will chemically react with the fats and actually tan the hide, making it safe to wear in the rain or high humidity.

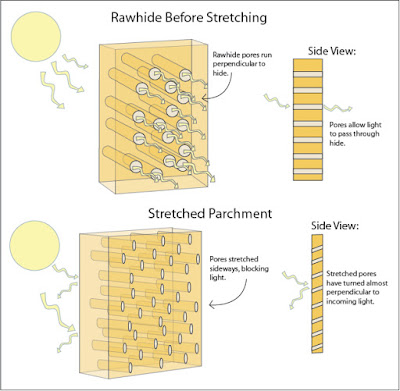

A plain, fleshed hide that is allowed to dry flat will be hard and smooth to the touch. With the fur removed, one can see that the dry, hard hide is translucent (or nearly transparent, if it is very thin). This is how rawhide lantern screens are made. The fibers making the pores of the skin still run from the outer side to the inner side in a relatively straight direction, allowing light to pass through the hide just as perspiration once passed through the skin of the living animal. Furthermore, the hard surface will not accept ink well (it is like writing on smooth wood), so this rigid, translucent material is not ideal for writing. It behaves rather like plastic; rigid, and not readily absorbent.

In order to make the skin turn white and accept ink, the wet skin must be stretched under extreme tension while it dries. This tension pulls the fibers of the pores sideways, making them lay down horizontally, while the collagen is still wet and flexible. As the skin dries out, the collagen dries and locks the pores in place in their new orientation. Thus, the stretched hide becomes opaque and white--but any area that does not get thoroughly stretched flat, while it dries, will end up translucent instead of white. Sometimes a thin skin may require a second stretching, or a rewetting and extra tightening of the tension, in order to get all of the translucent spots to stretch out and become white.

Unlike in buckskinning, this stretching is static. Instead of deliberately breaking the collagen proteins and creating a drapey, fabric-like material, parchment stretching merely strains the collagen bonds, to create a semi-flexible material that can bend only in one direction (like pages of paper). The thinner the hide, the more flex it will have (just like tissue paper, when compared to construction paper), but it remains more structurally stable than buckskin.

Directionality of stretching

Turning a 3-D shape with uneven thicknesses and amounts of flex into an even, 2-D sheet is not a simple process. Understanding how and where a skin is designed to flex, and where it is thicker or more rigid, will help the parchmenter work with the material efficiently.

The skin as it covers an animal is a flexible, bulging surface, with loose areas (like the stretchy skin at the joints/elbows, or under the chin) and tough areas (like the ridge along the spine), thin areas (like under the belly) and calloused areas (like the front of the knees, and sometimes the upper base of the neck). The texture of the pores and the stretchiness of the skin are very directional. The grain can resist stretching flat in certain directions, and pulling it tight enough to force it flat can simply rip the hide.

Therefore, the parchmenter trims off the parts of the skin that simply will not stretch flat without warping the rest of the skin (the legs, neck and tail) and discards those parts that are too fragile to withstand extreme tension (the sides of the belly). With a skin that now much more resembles a rectangle, the parchmenter can achieve a much more thorough (and thoroughly flat) stretching of the hide.

Trying to save too much skin results in an uneven stretch, causing wrinkles to set in the main body of the parchment. The more anchor points the parchmenter puts on the skin and ties to the frame, the more even the stretch, but there comes a point of diminishing returns. If in a hurry, then, the parchmenter can simply trim the skin to a rectangular or ovoid shape at the start and require fewer anchor points to achieve an even, flat hide at the end. Sections trimmed away are not wasted, for they make hide glue or hide-glue paint, and can be dried and saved as glue for future use.

In other words, efficiency results in a better product, while greed will lower the quality of the whole thing.

Storage

Parchment can be kept like paper, but it absorbs humidity and will not stay flat if too often exposed to moisture. Books were invented specifically to deal with this issue; the flat covers, bound closed and stored under pressure, kept the parchment pages flat even when humidity would have caused them to wrinkle.

Loose sheets of parchment can be displayed under tension, either whip-stitched to a frame, or pinned to a board. Glass frames can help to keep humidity out from the parchment display, but the glass must not be in contact with the parchment itself. Condensation or overabundant moisture will cause decay.

Wrinkles can be removed by resoaking and restretching the parchment, which works well if the goal is to remove the old ink or paint and scrape the page clean. Unfortunately, this method is very challenging if the goal is to preserve the writing or artwork. Museum curators sometimes succeed in gently moistening the skin, and stretching it between long, flat binder clips, without disturbing the scribal work. Such careful work may not be worth the effort, however; a few wrinkles in a looseleaf piece of parchment are perfectly period. It may be better to accept them rather than to risk the artwork on the page.

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions and suggestions for further research are welcome. No selling, no trolling, and back up any critique with modern scholarly sources. Comments that do not meet these criteria will be discarded.