Coppicing Part 4

The History and Sustainability of Coppicing

Part 4: Hedges

To read about other forms of coppicing, see Coppicing: Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

Definition

Hedges are lines of closely planted trees that form a barrier by growing together thickly. Fedges are living fences of trees, planted closely like a hedge, but carefully pruned to keep the trunks open and visible (the trunks are often woven in some aesthetically pleasing pattern). Hedges frequently reach 6' thick, and are allowed to grow with minimal edge-pruning for years at a time between pleachings. Fedges must be pruned yearly and only their tops become brushy and thick.

History

Hedges are as old as pasture divisions, and remain in use today. In WW2, hedge-rows in Europe were so old, well-rooted and impenetrable that they were able to stop tanks, and had to be blasted out of the way for machinery to get through. Unlike stone walls and wattle fences, hedges become stronger and better at containing livestock over time; with the same amount of maintenance, they become ever more valuable, while wattle fences must eventually be discarded and replaced, and stone walls must periodically be rebuilt from the ground up.

Fedges are, in terms of human agriculture, quite new; although grape vines were trained on trellises, fences and arbors, the training of woody plants to make living ornamental fences seems to have developed in the medieval period. This began with rose trees, trained into horizontal fence patterns and supported by traditional wooden fence rails. Gradually, however, this expanded to include the training of figs, and then other fruit trees, into living arbors and tunnel formations, and willow, hawthorn and hazel into living garden fences by the seventeenth century.

Hedges

Selecting species

The choice of hedge tree varieties depends largely upon purpose and location. Ideally, the plants should be native or well-adapted to the local climate, since they must be hardy and thrive without pampering. They should be chosen with forethought as to:

- their mature size

- their growth rate

- their suckering habits

- their likely spread (will they become a weed and take over the gardens or pastures?)

- their ability to cooperate with neighboring plants in the hedge-row (some have natural herbicides in their leaves or roots)

- their resistance to livestock, if applicable

- their resistance to local blights and parasites

- and their resilience in coppicing.

Thought must also be given to the period of time required for the hedge to reach a durable stage. Will there be fences in place to protect the juvenile hedge plants from hungry livestock? Will someone in the household be capable, physically, of pruning and laying the hedge in 8 years, or else have the funds to hire extra labor at that time? Can the young plants be watered, where the hedge will run, or should the plants be chosen for drought resistance? Once the hedge is mature, will it add value or detract from the property?

Generally, hedges should not include any toxic plants, plants that spread rhizomally, plants with aggressive seed spread, or evergreens that cannot survive coppicing.

Generally, hedges should include a mixture of species, some faster-growing and some slower, some with thorns if livestock are to be contained, and some that provide visual appeal or a useful harvest (flowers, fruits, nuts, medicinal bark, or firewood).

The most common choices include hazel, hawthorn, brambles (berry bushes), buckthorn, blackthorn, elderberry, rose, goose berry, barberry, holly and willow. In North America, osage orange and locust are also common choices (although both come with a warning about aggressive spread).

Preparing the row

Soil preparation for a hedge is as important as soil prep for planting a tree. The root system needs to grow quickly, and receive plentiful nutrients, to provide a strong base for the above-ground hedge. Because most of the species chosen for hedges are very fast-growing in their first years, and fast-growing again when they are cut back, the soil needs plenty of food to feed their growth.

First, the row needs to be planned and marked out to check for conflicts. This hedge may last for centuries, if cared for, so it is worth thinking carefully about its best route down slopes, or through boggy grounds, under power lines, etc. It can block the wind if correctly oriented to provide a buffer, or it can provide afternoon shade to livestock—or it might shade out a vegetable garden, or drop leaves into a swimming pool, if poorly placed. Running it straight down a slope may not be as beneficial as gently angling it to help prevent erosion. Placing it away from a boggy area may help prevent future dead spots in the row, or make it easier to prune and maintain.

Next, the soil should be dug up and mixed with compost, if feasible. If the row will be so long that deep digging and mixing is impractical, then at least disturbing the surface and adding a piled mulch of compost will help to provide the nutrients the hedge will require. In some cases, a preparatory hedge might be advisable; some plants, such as willow, may take root even without pre-digging the row, and their roots will deepen the tilth of the soil until other hedge plants can be interplanted among them.

Thomas Hill, in The Gardener's Labyrinth (published in 1577), recommends in Chapter VIII digging the row for hedge planting about 2-3' wide and half a foot deep. He also suggests digging two rows, parallel and 3' apart; this creates a double hedge, for added strength against wind, livestock or human prowlers, although this may make future hedge laying more difficult. According to him, Columella, in his Husbandrie, further suggests doing this digging in the Fall and leaving the furrows open all winter. Doing this allows the turned sod to decompose, so that the dirt is easier to put back during planting. However, in areas with heavy winter rains, this is also a good way to lose most of the soil fertility to erosion. Modern methods to rot the sod include row covers (even cardboard, laid down and weighted with rocks) or simply piling mulch or barn manure and straw on the intended row.

Protecting the hedge

Weeds are the chief enemy of a newly planted hedge, and grazing by livestock or wildlife is the second biggest threat. Thought must go into preventing both before the hedge is planted.

Where available, plastic weed-block-cloth is the simplest solution to the first. Laying two rolls of it, so that a 6' wide row with the planting furrow in the center, is ideal, but even one 3' wide roll with holes cut in the center for each plant will help. The hedge will become more vigorous over time and its roots will store sufficient energy for fast regrowth after cuttings, so weeds will be less threatening once the hedge matures, but the plants must survive their first year in order to reach that point. If choked by weeds, they are wasted; all will struggle and some may die.

The medieval method for weeding long hedge-rows when they were young was scorching, similar to the weed-burning flame throwers today, but carried out with a burning torch of bundled straw. Thomas Hill also claims that scorching helps stimulate hedge growth and recommends using fire to prune the sides of the hedge during the growing season (presumably during a wet growth period, so that the hedge does not start a wildfire). They also practiced mulching, which is an excellent option for natural weed suppression today and has the added benefit of providing future fertility as it decomposes. Manual weeding with a hoe, several times during the growing season, is another option.

To keep livestock and wildlife from eating the tender new growth from the hedge, a fenceline on either side of the hedge (and with space inside so that the farmer may tend and weed the plants) is helpful. The hedge needs to be protected for years, and cannot be trusted to contain livestock for the first 8 years. Goats and pigs, in particular, will damage the young bark and root systems of an immature hedge. They must be kept away, or only allowed to graze near the hedge in brief, monitored intervals.

Two lines of electric fence are an easy modern solution for keeping out livestock. Although goats will certainly jump over a short, two-wire fence in normal circumstances, they are less likely to jump over electric fence into a bush that they perceive might dump them back onto the fence. With cattle and horses that are trained to electric fences, only a single wire may be required to keep them back from browsing on the hedge. This has the additional benefit of letting them graze slightly above and below the wire, trimming back the hedge away from the electric line and mowing some weeds away from the hedge base, without allowing the livestock to reach the trunks of the hedge itself. On the down-side, however, electric fences do short out when too much plant matter comes into contact with them; the hedge needs to be trimmed back from the electric lines manually if the livestock do not succeed in reaching it around the line.

Alternatively, a dead brush fence can be placed on either side of the newly planted hedge, especially in regions where aggressive weeds and vines are less common. Unfortunately, this makes access for weeding more difficult and is labor-intensive to carry into place, not to mention aesthetically unappealing in a less agricultural setting. This has the advantage of adding future fertility to the soil, like mulch, but the disadvantage of hosting a variety of pests that may hide beneath the piled debris (rodents, snakes, insects, foxes and so on).

Finally, a quick-set hedge of willow panels can provide a boundary on either side of the future permanent hedge, if livestock will not be penned too long in the pasture with it. A wattle fence can also be built, but this is even more labor-intensive. Setting wattle hurdles in place as a solid fence to protect the hedge, section by section, can help at least make this a reusable labor expenditure.

According to Thomas Hill, a fast-growing, thorny bramble hedge must be protected from livestock for at least the first 3 years.

Planting

Seeds, dormant living stakes, bare-root saplings and transplants are all legitimate options for starting the hedge. The further advanced the plant is in care and maturity, the better its chances of surviving and growing quickly, but also the higher the cost in labor and sometimes expense.

Thomas Hill recommends both the planting by seeds and the planting by dormant stakes:

For seeds, he says to gather the berries and seeds of the various plants desired, and mash them together to make a juicy berry paste full of seeds. Then, he says to find a large, rotten rope (like a ship cable or a well-bucket rope) that is fraying and decaying so that the fuzzy fibers stick out to the sides. This should be smeared with the berry seed paste until well saturated and the seeds are glued all over the rope, well-massaged into the fuzz. The fuzz, he says, will protect the seedlings from cold in early spring. This rope can be dried for use in the following spring, or else put into the furrow immediately and covered lightly with dirt. With watering, it sprouts all of the various species that were mashed together, intermingled and hopefully in a roughly even mix.

For stakes, he instructs that thick canes of bramble or briar or osier (willow) be cut into short sections, and these placed upright in the open furrow, in early spring. He says that they must be watered diligently and that the soil around them must be hilled up against them frequently until they are growing well (hoeing to prevent weeds). He also refers to a quick-set hedge, which is simply a panel of live willow stakes, lashed onto two cross-bars (like a raft) and set upright in the furrow, then back-filled and watered.

Modernly, setting live stakes (cut from coppices or pollards while still dormant but as winter comes to an end) into prepared soil is the most common way of starting a hedge. Transplanting saplings, bare-root or with root balls, is far more expensive, but it does save time in getting the hedge ready to contain livestock and makes weeding less of a priority (it still needs to happen...). Cut the stakes about a foot long, and bury them UPRIGHT (the buds must point up the way they did on the tree) with only about 4 inches above the soil. Water them diligently but not to the point that they could rot. Leaves and branches will grow after warm weather and sunlight stimulate the stakes; water at this stage is critical because the cut stakes have no root system to harvest water on their own yet. Fill in gaps with more stakes if some die.

Monitor and weed the baby hedge all year, and if the winter is likely to be harsh, consider adding mulch to protect the young root system. Do not cut back the young growth, since the goal here is not to make a yearly harvested coppice but to make a thick, mature hedge.

Pleaching

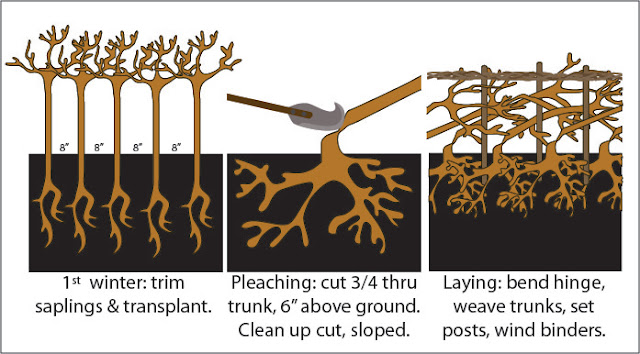

Hedge-laying is a hybrid of coppicing and pollarding. The above-ground section of the tree is not completely cut, so it is not exactly coppicing, but the cut occurs at ground level and stimulates regrowth from the stool, so it is not exactly pollarding, either.

The laying of a hedge has to be done cyclically, usually every 8 years or so. If it is neglected, the hedge becomes too tall and old, with consequent die-offs and thinning. The goal of laying the hedge is to make it grow back thicker and stronger, with a framework of horizontal bars forming an impassible barrier to even the most determined livestock (bulls and boars), and keeping the trees in a perpetually juvenile state so that they stay alive indefinitely. Furthermore, hedge-laying trims back and cleans up the lateral growth of the hedge, making sure that it does not spread and eat into the valuable pasture, field or garden space it protects.

Before laying a hedge, the farmer must collect enough stakes and enough binders to secure the newly laid hedge. Laying a hedge without these stakes and binders leaves the fragile hinges of the cut pleachers vulnerable to wind or animal disruption and might result in broken, disorderly cut sections of hedge flopped around on the ground beside their stools. The stake should be a straight length of hardwood, usually from a coppice grove, 5' tall and about 1” in diameter. Plan to grow a coppice or pollard to supply enough stakes to place one every 2' along the hedge line. The bottoms of the stakes need to be sharpened (two angle-cuts with the billhook will do). The binders should be 8' long, flexible rods (willow serves well) about 1” in diameter (but thinner can work). Gather enough binders to lay 4 together along each segment of hedge, with some overlap, for the whole length that needs to be laid.

A rule of thumb for estimating the number of stakes and binders: 2 stakes and 2 binders per yard of linear hedge.

The first step of hedge-laying is pruning. This is usually done on both sides of a hedge, although it can work if done only on one side. A good reason to leave one side bushy is if the pasture on that side will have to enclose livestock again soon; losing the use of two pastures, rather than just one, while waiting for the hedge to recover, is harder on a farmer and the pasture soil.

In winter, the farmer trims and prunes away all lateral growth from the trunks, clearing the whole side of the hedge to gain access to the roots and trunks. These prunings may be useful firewood or used as a dead brush barrier to protect another new hedge planting. If absolutely necessary, they can also make a dead brush barrier along the hedge they came from, after laying is finished, but this may make the necessary pruning of the newly laid hedge difficult, so it is better if the farmer can avoid using that field much or protect the hedge with electric fence instead. Finally, the farmer cuts all brambles, weeds and saplings that are in the way or do not belong in the hedge.

When the 'diversions' are cleared away, the farmer selects the pleachers. If there are too many good stems and trunks in the hedge row, the farmer thins these selectively to leave only the most vigorous and usable, choosing straight, thorny trunks that grow on the center line. If too few vigorous candidates remain (this happens in a neglected hedge that has not been coppiced in too long), the remnants should be pleached and new living stakes should be added between them.

Working from the top, laying the pleachers uphill if the ground slopes, the farmer uses a sharp billhook to chop MOST of the way through the trunk, leaving a hinge. The cut must angle down, making the movement with the billhook almost a vertical slash, not a horizontal strike. This divides the trunk to make a very short split piece and a thin hinge connecting to the urpight pleacher. This pleacher is laid on its side gently, in the direction of its hinge. Then, with a bowsaw (or the billhook if sufficiently skilled), cut the remaining stub of the trunk, or heel, off, to make a clean coppice stool close to the ground, being VERY careful not to cut the living hinge by accident. If the hinge is severed, the pleacher dies and serves no purpose in the hedge.

Note: if the pleacher or trunk is thicker than 3” diameter, switch from the billhook to a small chainsaw or an axe. If the wood is older and less flexible, leave a thicker hinge than normal.

Work the bushy upper section of each pleacher into those laid before it, using the billhook if needed to trim or make shallow cuts for additional hinges in the upper branches. These need to lay in a straight line and be tucked in together well, for security. Roughly every 2', the hedge will need a stake driven down through the layered brush, navigating around the trunks of the laid pleachers, and pounded into the soil enough to hold it in place. Alternate between laying a few pleachers, and setting a stake, so that the distance from the last stake never gets to be so great that the hedge risks slipping over sideways; this could tear the hinges.

As the laying and staking proceed, the hedge will need reinforcement from binders. Binding begins by tying a couple of binders together at the end with twine, and weaving a pair around the stakes like wattle, starting at the first stake and working toward the most recent cuts. Then a second pair of binders is tied together at the end, and woven around the stakes on the opposite sides from the original pair. One way of making this binding even more secure is to twist the two separate pairs around each other as they weave between the stakes. There are more complex weaves out there, for those who enjoy braiding.

To continue binding, slide new binders in between the pairs and continue their pattern, working down the row of stakes until too close to the last stake. Then pause and go back to laying and staking for a while. Work at this, alternating binding periodically, until reaching the end of the row. Be sure to leave some upright brush at the end of the row to prevent gaps while the hedge recovers, but do not leave any pleachers uncut, as this will weaken them. They need the continual coppicing to stimulate healthy regrowth. Weave the binders over the final stakes and push the last ends down into the brush.

To finish, walk the row, driving each stake down a little deeper and tapping the binders down tight against the layered brush below them. Use a wooden maul for all of the driving, to avoid damaging the stakes. Finally, the stakes can be trimmed with loppers (or not; this is purely aesthetic).

Weed the newly laid hedge during the growing season, and trim back the new growth the next winter, just to a bit above the height of the stakes. Prune back lateral growth to about 3' from the trunks. The next two winters, trim the hedge to about 8” beyond its previous year's growth. This stimulates thick growth inside the hedge, rather than letting it sprawl out and weaken.

After those first 3 years, the hedge should be sound for another 5 years or so without much interference. Checking for aggressive weeds, die-offs, spreading or areas getting too tall will help save labor later, however. It is a good idea to do a little maintenance on all of the hedge rows every winter.

Fedges

Species

Willow is the most common living fence species, because it grows very quickly, roots easily without much soil prep-work, provides withes for basketry or wattle, is pleasant to look at, and comes with very few pests, or downsides. One downside, however, is that the root system takes hold very strongly and will not be removed easily. Where a living fence is planted, there it stays. Cutting it down will simply coppice it (even in summer). This is important to consider when deciding where to plant it, because the living fence will always require pruning and must not be allowed to grow out of control.

Roses were commonly trained into living fences and hedges in the medieval period. These were typically smaller fencelines, around an herber or prayer garden rather than around a full kitchen garden. These do require a trellis or frame, or a split-rail fence, or posts and wires, to support the roses as they grow and allow for more intricate training.

Since many detailed overviews of rose training and care already exist, however, this next section will focus on willow fedges.

Planting

Willow stakes can root in almost any fertile soil, so long as they receive adequate water. A row of weed-block cloth may be sufficient preparation for a living willow fence; simply jabbing the pointed ends of the stakes into the ground in early spring will get them started. However, digging the soil and adding compost will improve their performance.

Planting begins with collecting long willow withes (about 8' long) from a coppice. It could also start with cut sections (about 1' long) of thicker rod, harvested from willow branches. Thick, short stakes will typically root better, where the withes may not all take. However, training the growth from the cut stakes takes more labor, throughout the growing season, while starting with long withes will skip most of the later work. Therefore, start with long withes.

Mark the line of the fence on the ground, and prep the soil if needed, and place weed-block cloth if needed. Pound 5' stakes into the ground, leaving 4.5' above ground, following the marked line and at roughly an 8' spacing. Run a taut wire (or twine) between the stakes at 4' above the ground.

Insert withes into the soil at a 45º angle, staying on the marked line, and with the angle in the same line as the marked line on the ground. Push them to an 8” depth and space them 2' apart. Where they meet the overhead wire, running straight from their angled entry into the ground, wrap the narrow end of the withe around and around the wire for 2' and tie it with twine; leave any excess loose for now. When the next withe reaches the wire, wrap it likewise, starting by overlapping the tail of the last if it had excess length. Continue this to the end of the line. Then, go back and insert withes halfway between each of the previous withes, working at a perpendicular angle to the original angle, weaving downward between the withes already in place (over, under, over, under) until the new withe reaches the ground. Insert them at the opposite angle to the original, and push them 8” into the soil. Wrap the long ends around the wire, twisting opposite of the original direction.

At the end of each line of withes, the final few will not intersect with the overhead wire. Instead, they will reach out past the post into empty space. Secure them to the post with twine and prune off the excess. The last one will be very short indeed, but it may grow more vigorously for that.

The woven withes should create a lattice of square openings, with a withe pushed into the ground every 1' along the line, and the long ends of the withes wrapped around the upper wire in a thick cable.

Any excess sections of the withe tail ends, or parts along the wire that broke during wrapping, can be pruned now. The start and ending areas of the fenceline will have fewer weavers and some straight sections without squares; this is normal.

Water the newly planted withes well and often; do not swamp the ground, but keep it moist. Willows are thirsty and these new willows have no roots, as yet, with which to drink. This is especially important on warm, sunny days, particularly when they have leaves.

Training

Allow leaves to grow all along the fence as it tries to harvest sunlight and set roots. Do not, however, allow branches to grow anywhere except along the top wires. To remove the start of a branch, pinch it or scrape it from the withe.

The one exception to this bud-removal is on the final withes, at the ends of the fence line. These, having been trimmed and tied to the posts rather than reaching the top wire, still need branches and leaves to survive. Allow them to grow branches, but train the branches up, back into the weaving, and eventually wrap their ends around the wire with the rest. Once they have branches well established along the top wire, treat them like the others.

In winter, prune the fence back to its original height, cutting the new growth close to where the original withes were wrapped around the wire. Try to cut back to these exact points every year after this; they will form a pollard and heal faster as a result.

In the next spring, branches will again emerge from the top line. This time, scrape all buds from the withes anywhere in the lattice; only allow leaves and branches along the top wire. Early and often is healthiest for the willows; catching the bud as it forms will rob the young tree of less energy than waiting until it has formed a branch that has to be cut off. Monitor the slender trunks every week and remove unwanted buds each time. The top wire will grow a tall, bushy hedge of willow branches and leaves, while the woven trunks below thicken and adjust to their training.

Every winter afterwards will include cutting back the top of this hedge to the original wire-wrapping. Do not neglect it, or the weight of the branches will make the fedge top-heavy and unstable. The harvested branches can be used to start further hedges or fedges, or for basketry, or for livestock fodder.

Check for unwanted buds every spring and summer and remove them, and watch to see if pressure grafting occurs.

Mulch the roots of the willow fedge with compost to continually provide nutrients. Cutting the new growth every year will help stunt the trees and keep the trunks narrow, and prevent the roots from growing excessively, but it will also eat up nutrients in the soil over time. Willow coppices that are cut annually help harvest and clean nutrient loads from compost toilets and humanure brown-fields precisely because the willow is greedy for nutrients. Feeding it is important.

Sources:

Maclean, Murray. Hedges and Hedgelaying. Crowood Press Ltd, 2006.

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions and suggestions for further research are welcome. No selling, no trolling, and back up any critique with modern scholarly sources. Comments that do not meet these criteria will be discarded.