Coppicing Part 3

The History and Sustainability of Coppicing

Part 3 of 4: Pollarding

Definition

A pollard is like a coppice, except that the tree must be trained to the purpose from a relatively young age, and the above-ground section of tree is not completely removed. Instead, the tree is allowed to retain the first section of trunk and sometimes a few side-branches. Then, the annual growth is cut and harvested every winter—or, in the case of fruit tree pollarding, new growth is pruned away during the growing season.

Pollarding is designed for a pastoral system or a domestic yard, rather than a forest system. The goal of a pollard is to combine livestock pasture, or home and garden areas, with useful wood or fruit production (especially slender withes for making baskets or wattle), all with a minimum of risk to the tree and to the human settlement.

A pollard is kept artificially short, so that it never reaches a dangerous height (it cannot fall on structures or fences or livestock), and so that its fruit or branches are readily accessible for harvest from the ground or with a ladder. Collecting its yearly growth by cutting the shoots uses up most of the tree's energy for growing, so the root system remains smaller than normal and its trunk grows much more slowly.

History

Pollarding is an extremely old method of producing rods and withes, documentable at least as far back as ancient Egypt; tomb wall paintings depict pollards, where the trunk is thick and shoulder-height but only has bunches of very thin, straight rods abruptly emerging from it. Wherever wattle fencing is common in the archaeological record, it is safe to assume that the builders either practiced coppicing or pollarding, since those are the basic methods of generating a large harvest of narrow-diameter, straight, flexible rods for weaving wattle hurdles and fences.

Evidence also points to the pollarding of trees in gardens, especially fruit trees, in Classical villas and their walled gardens. The garden at Villa Poppaea, for instance, has been extensively excavated and studied, and tree holes were found in close proximity to structures. Even more definite evidence comes from Pompeii, where fruit trees were planted for extended periods directly against the garden walls (about 6” from the walls) and yet did not damage the foundations. Since, at this period, new tree types were being imported and introduced into Roman gardens from warmer climates, it is safe to assume that the trees required the protection and thermal mass provided by being trained along the walls. Planting a tree 6” from a wall requires training the tree in a 2-D plane, so that branches do not exert pressure on the wall, and placing roots so close to foundations would threaten the integrity of the wall if the tree were not being kept in a stunted growth pattern.

However, our best evidence for pollarding in history comes from writings like Pliny the Elder's book, Natural History, circa 71 CE. Pliny describes imported trees that have been pollarded, like balsam: “when it puts forth branches it is pruned in a similar manner [to grape vines]” (1), and he details the uses for the branches that are pruned away every year (medicinal bark, the shoots boiled for unguents, and the wood for perfume). Other Classical writers likewise refer to the pruning of trees for a constant harvest, mentioning trees like the plane tree and willows.

Later illuminations, throughout Europe and into Persia, showing pollards planted in rows, or along water ways, in fencelines or next to walls. Such illustrations abound up to the end of the medieval period, and pollards have remained in use even into the industrial period.

Selecting a tree

Most types of tree can be pollarded while they are young, but pollarding is not appropriate for all types of harvest. Firewood and large poles should not be grown on a pollard, but should be coppiced instead; the weight of the harvest on the branches should never be allowed to get so heavy that they would risk the branches breaking off, as this harms the tree.

Although some types of evergreen can tolerate being trained in this manner, it is rarely done, since there is risk of the tree bleeding too much when cut. Holly is an exception.

Willow, hazel and hawthorn are commonly pollarded, to produce withes for basketry and wattle. In North America, osage orange can also be treated this way for hedge stakes and bow wood.

Fruit trees are the next most common choice for pollarding. Here, the objective is to train the tree to remain accessible, while keeping its limbs in a semi-juvenile state so that they produce fruit indefinitely. Sometimes training a fruit tree may also take a very artistic or sculpted form, such as espalier or cordon or Belgian fence. Nut trees, too, may be pollarded if the goal is to harvest them manually from the branches (not wait for the nuts to fall to the ground). Hazelnuts, for example, are very popular with wildlife and livestock; the gardener may not be able to collect any if they are allowed to fall to the dirt.

Medicinal bark can likewise be harvested from pollards, where the annual shoots are collected and stripped of their bark to make painkillers, like willow-bark tea, or astringents, like witch-hazel, etc. Flowers may also be the objective, such as hawthorns and roses, both of which respond very well to pollarding.

Other hardwoods can be pollarded if there is a need; maple, oak, birch and others can be managed this way under power lines overhead, or if there are concerns about buried utilities. This is a very safe way to keep shade trees near structures or against walls without worrying that they will fall and crush the structures, or damage the foundations.

Training

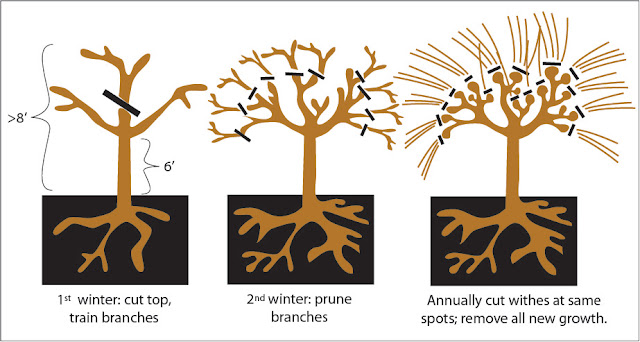

To start a pollard, the young tree is cut in winter, usually 4-6' above ground, leaving the first length of trunk but removing the top. This is called heading. The tree should be more than 8' tall before this is done, and ideally it should have a few side-branches already. These side-branches are now ready to be trained into any special shape that the forester plans, or they may be left in their natural shape after the heading cut.

In spring, the tree trunk puts forth new shoots from around the cut—just like a coppice stool, but up at a height where grazing livestock, like goats, cannot reach these fragile shoots. The existing branches continue to branch outward through the growing season. If a special shape is desired, training has to be continuous during the growing season of this first year. Any new growth should be tied to the guiding wires or frame, or else pruned away as soon as possible so that the tree will not dedicate valuable resources to that incorrect direction.

In winter, the tree can be pruned back again, this time to the forks of the new branchings. The following spring, the tree will grow new sprouts where the pruning occurred, and these are pruned at the same location every following winter. Thus the tree will form bulbs of knotty wood, called polls or pollard heads. Pollard heads heal very quickly, and store extra energy for putting forth new shoots every year. So long as the forester continues to harvest the withes from the same location each pruning season, the tree will thrive. The more routine the schedule of this harvest, the better for the tree; it will adapt to the normal removal of its new growth, and its immune system will be ready for its regular pruning.

Training special shapes varies, depending on the shape, but once the established shape has been trained into the tree, the main labor is to keep it pruned back to that shape. For the first several years, this will include pruning during the growing season. Eventually the tree may adjust to the shape and put less effort into trying to deviate from it, and more energy into fruit or flower production; in this case, the pruning can occur annually.

Benefits of pollarding

Pollarding is especially useful in orchards and pastures, where livestock can graze in the shade beneath the trees—mowing the weeds, but unable to reach high enough to harm the new shoots, or steal the fruit. The pollarded trees provide shelter and shade for livestock, and their roots anchor the soil against erosion. The livestock provide fertilizer, soil aeration and weed control.

Pollarding and pasture particularly go well together if the intended harvest is stick hay, or fodder withes. This is a method of feeding livestock in winter, wherein the farmer cuts the leafy shoots from the pollards every fall before the leaves drop, and stores them dry for fodder. The livestock do not only eat the leaves, but also parts of the shoot and usually the bark, accessing minerals and vitamins not provided by normal grass hay. Willow is the standard choice for fodder pollards, since it grows very rapidly and tolerates early-season cutting when the leaves have not yet fallen.

Because the trunk is allowed to gradually mature, the bark becomes thicker over time and resists injury by livestock. It must still be said that a bored goat will strip the bark, even if the trunk is mature and the bark is not tasty, but in most cases the mature trunks are safe even from goats, as long as there are other things to eat. Fruit trees, however, should never have goats grazing under them for long. The bark is sweet and forms an irresistible temptation, even when it is thick and scaly.

The pollarded state of perpetual youth in the branches is important for fruit production. An old fruit tree will no longer produce as much fruit as in its prime. Replacing the old tree with a new sapling wastes labor (in transplanting the sapling) and many years of slow development, as the sapling matures enough to finally produce fruits. If the orchard keeper pollards the tree from the start, however, it will never reach that slowing of production experienced by old fruit trees. An orchard of pollarded fruit trees can maintain a constant supply of healthy fruit without losing the time needed to establish saplings, or wasting labor in removing and replacing old trees. When old branches must be removed, new ones are trained to take their places. Note, however, that this is not a very safe treatment for grafted varieties. Cutting back too close to the trunk of a tree will remove the grafted variety and allow the root stock to grow instead.

Pollarding a tree also extends its lifespan, sometimes by several times its normal life expectancy. This stems from the constant removal of new growth, which deliberately stunts the tree and reduces the amount of energy which it can put toward expanding its trunk. As explained in Coppicing Part 2, a tree's life is limited by the ratio of deadwood to living sapwood. If the tree spends less on building up the inner, dead heartwood, then the time when there is too much deadwood for the sapwood to support is postponed. However, unlike coppicing, pollarding cannot make a tree immortal. Eventually, the above-ground portion of the tree will become too old and the trunk may even grow hollow. Pollards rarely live more than a few centuries.

To continue reading about alternate forms of coppicing, see Coppicing Part 4.

Sources:

1) Pliny the Elder. The Natural History. Translated by John Bostock, M.D. Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University. Book XII.

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions and suggestions for further research are welcome. No selling, no trolling, and back up any critique with modern scholarly sources. Comments that do not meet these criteria will be discarded.