Irish Garb Part 1

Early Medieval Irish Garb Part 1: Analyzing Sources

Background

During the prehistoric period in Ireland, the insular Irish developed unusual laws, clothing and habits, relatively independently from the Continental trends of the time. Thanks to their island status, their material culture seems to have continued with few changes for many centuries, from the Iron Age onward. According to Barry Raftery, the Irish had a tendency to thoroughly assimilate anything new into their existing culture, art, and economy, without themselves being much changed by its adoption: “this illustrates well the recurring conundrum of Irish prehistory. Here we have something that is totally new in the country, yet rendered in a form that is different in detail from anything in the area of presumed origin.” (1) Thus, the Irish managed to hold on to a pastoral economy of grain, pig, and most importantly, cattle-raising, with a dispersed population on decentralized family holdings and a tribal style of chiefs and kings, in a very stable pattern of dwelling, economy and political structure, through a period of growth and increasing wealth from 200 CE to around 1200 CE.

Christianity reached the island in the 400's CE, bringing writing, ecclesiastic hierarchy, and saintly cults, but it appears to have altered little in terms of secular garb and lifestyles. Literacy spread, and the Church secured a strong political power, but material culture seems to have remained stable.

The Viking incursions in the 800's CE likewise seem to have changed little of the local apparel (except, perhaps, the brief use of the warp-weighted loom). Although the Viking towns did create the first urban environments in Ireland, with subsequent market economy increasing over the years, and trade certainly improved during this period, life for the average Irish farmer would likely have been much as it had been centuries earlier.

The Norman invasion and conquest of Ireland, however, forced dramatic changes in economy, property transfer, politics and, eventually, dress. As a conquered people of a colonial power, the Irish found their ways gradually suppressed as their resources were exploited for foreign profit. Thus the traditional Irish ways gave way (not without resistance) by the mid-1300's CE, and Irish dress lost permanently most of those aspects which had previously made it unique.

Unfortunately, centuries of suppression under English rule destroyed many records that might have provided details about the ancient Irish culture. Furthermore, Victorian “Celtophile” writings (and the eugenics movement that influenced early historians) sadly muddied the waters (see Insular, not Celtic). This resulted in popular notions of early Irish dress that were tragically inaccurate, and even today linger as a challenge for modern reenactors to overcome.

Happily, thanks to the recent efforts of archaeologists, translators and archivists, a wealth of new information is currently pouring out of Ireland—making research into Irish material culture suddenly more feasible. Modern efforts center on correcting errors, increasing the accuracy of translations and improving access to new archaeological discoveries.

Commonly Cited Sources

Much of the information publicly available documenting Irish clothing depends on a few early (mostly 19th century) translations of Brehon Law and the Irish Annals, along with a few woodcut images from the late 1500's CE. Unfortunately, early errors have been cited, repeated and depended upon for so many decades that it can be difficult to sift through them for correct information.

1. The earliest modern historical attempt to understand old Irish dress comes from Eugene O'Curry's lectures, published posthumously in Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish (1873), and his work with John O'Donovan and a team funded by the British Government for the task of translating ancient Irish law. Sadly, due to misinterpreted language and some cultural bias, these produced many false understandings of Irish culture and custom. This is not to disparage the effort O'Curry put into the massive task of translating thousands of pages of ancient Irish records from aging manuscripts.

However, O'Curry specialized in Middle and Early Modern Irish language, not Old Irish, and could not grasp the subtleties and technicalities represented in these legal works. In one often-cited example, O'Curry mistranslates “leine” (the Irish word for a linen tunic) as “a kilt,” and he goes on to defend his belief in Irish kilts, in depth, ignoring any indications to the contrary (such as that some lente having hoods attached to them, which would be hard to imagine on a waist-to-knee kilt).

2. Patrick Weston Joyce, author of Social History of Ireland (1903) and A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland (1906), referenced O'Curry for many of his sources and adopted his belief in the mistranslated or misinterpreted concepts, such as the kilt. Thankfully, not all of his citations depended on O'Curry's work, and not all of his information was wrong; Joyce's books still serve as a useful overview of artifacts and finds from Ireland. One major problem in his work was his routine neglect of historical context; he cites wood-cuttings from the 1500's CE alongside poetry from the 700's CE and archaeological finds from the Bronze Age, trying to force them all to fit together into one unaltered culture when many centuries of major social change segregate their contexts. Both Joyce and O'Curry helped shape modern scholastic interest in ancient Ireland, but using or citing their findings and conclusions requires caution. Any works citing them without other, corroborating works (ones which do not also depend on either Joyce or O'Curry for their information) should be tested for validity by extensive fact-checking.

3. Henry Foster McClintock provides the next major source for analyzing Irish garb. In 1958, his Handbook on the Traditional Old Irish Dress expanded upon the initial work he had put forward in his 1943 book, Old Irish and Highland Dress. Though more research, images, manuscripts and archaeological finds have become available since McClintock's time, these books still encompass much of the known Irish customs in clothing, and provide a useful overview. McClintock had a humble and pragmatic perspective on documentation—he recognized his own lack of knowledge of the ancient Irish language, which he points out in his first pages is not the same as more modern varieties of Gaelic, and therefore refrains from using much of the text then available for documenting his garb research (saying that he cannot verify the translations of the words involved). This book provides an excellent first step for anyone who wishes to study Irish garb—though it is not the final word on the subject, as current archeology continues to uncover new information.

4. Mairead Dunlevy published a more complete overview of Irish clothing through the ages in her book, Dress in Ireland (1989, republished in 2000). Dunlevy's interests in dress included modern designers, Irish lace-making history, poplin and other 18th through 20th century fabric uses, jewelry, glassware, etc. She curated at the National Museum of Ireland for many years, and her research had a solid foundation on actual finds housed in the Museum. However, her analyses lack much detail that would help in reconstructing these garments. She clearly prefers the more recent ages of fashion, and gives only a scant overview of earlier garb. Her single chapter on pre-1300's CE Irish dress tries to encompass everything from prehistoric and Iron Age clothing to garb in the Norman conquest, in only a few pages. The synopsis of garb from such an expansive time period is necessarily broad and generalized, with very few hints on how such clothing could be reproduced. She examines only one of the manuscripts available of Topographia Hibernica—an inferior copy—for her source on Irish clothing during the Norman period. Thus her information for Irish garb prior to the 1300's CE is limited. Still, her book provides an excellent introduction into Irish clothing trends, with a bibliography to point the way to further research.

Many other works exist studying the Irish art, metalwork, history and lore; for instance, Karl S. Bottigheimer's work Ireland and the Irish: a short history covers much of the historic trends in population and politics in Ireland. A.T. Lucas's 1956 study of “Footwear in Ireland” examines the evidence then available for how the Irish made their shoes. However, many of these works are now out of date, as new information has come to light since their publication, so their conclusions must be read with that caution in mind.

Additionally, early Irish archaeological studies rarely mentioned textiles or leather, being more extensively interested in treasure and weapons. Of course, this stems in part from how well metals and gems withstand the Irish climate, unlike textiles. In most cool, damp northwestern European climates, “fibers made from animal protein can survive in good order while cellulose vegetable fibers cannot” (2). This makes locating extant pieces difficult and leads to the mistaken assumption that northerners only wore wool—an assumption provably wrong, but easy to make if one acknowledges only extant pieces of garb, without literary or artistic context.

Extant Pieces

Bog bodies and bog finds, where the cool, acidic, anaerobic environment tans and preserves skins, leathers and sometimes wood (though usually not bone), sometimes include textiles. The Moy Bog dress, for example, survives in amazing condition despite its age (ca.1400 CE) thanks to the bog where it was abandoned. Sadly, most of the existing bog textiles come from pre-industrialized peat mining, where humans with shovels encountered bodies or other articles embedded in the peat and stopped work to investigate. Today, mining machines used for milling the peat often massively damage or outright destroy the finds before operators notice their presence. This leads to a sad conundrum; older finds which were uncovered intact and relatively undisturbed were often poorly preserved after their disinterment, frequently leading to their disintegration or at least decay. Many of the treatments applied to keep them whole for display have ruined the chances of chemical analyses and dating. Meanwhile, modern methods for preservation would allow such finds to be kept in good condition and examined more completely by textile experts, etc.—but few finds now come to light, as modern machines shred the artifacts. Those few textile finds retrieved from bogs are often difficult to analyze, thanks in part to the attempted preservation techniques, and in part to the chemical changes inherent in bog immersion (red and brown coloration, etc). Skin products reclaimed from bogs are invariably tanned by the tannins in bog water, and so the tanning methods (or lack thereof) of the shoes, bags, etc cannot be determined.

Outside of bogs, textile and leather finds often come from waterlogged sites (shipwrecks, crannogs, etc), indoor storage (grandmother's old trunk of heirlooms in the attic, etc.), or else from salt mines, deserts and glaciers. In Ireland, most indoor treasures were deliberately destroyed by conquerors who felt the need to suppress Irish nationalism during many centuries of foreign rule. The Irish climate provides neither deserts nor glaciers, and documenting textiles found in Continental salt mines as belonging to Ireland or people of Irish origin is exceedingly difficult. Some fragments of textiles have been luckily preserved in graves and the dirt of early settlements. Archaeological digs since the economic boom called the Irish Tiger have been more comprehensive in documenting these finds and preserving them for further examination. However, most of what is left comes in tiny scrap form and rarely gets much publicity outside of the archaeological community.

Primary Sources

Beyond extant remnants, primary sources for Irish garb include art and literature of the period. Manuscripts sometimes include illuminations with humans depicted in Irish garb, with various degrees of stylized artistic rendering. Relevant manuscripts include some from Irish monasteries (such as the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Irish Evangelary from St. Gall (3)). There are also manuscripts by contemporary authors in Continental Europe who wrote down hearsay about the Irish (the least reliable of period sources). These illuminations and written depictions range from relatively realistic to clearly abstract or third-hand, and can be cited for garb documentation only with awareness of the limitations of the medium and the bias of the authors involved.

Relief carvings on statues, effigies, crosses, reliquaries, church walls, etc. can also offer clues into the clothing experiences and expectations of the artists creating them. Where details can be made out, the garb portrayed can inform the researcher's understanding of what the artist may have been accustomed to in local dress. However, this again must be approached with caution. Many such carvings have religious context and were meant to portray figures from Biblical stories or hagiographies, sometimes with deliberately foreign garb or styles of artwork. For example, according to David Wilson, the bronze relief figures on the Shrine of St. Manchan represent the Irish interpretation of Scandinavian artwork (the Irish Urnes style, early 1100's CE) and portray at least one Scandinavian saint, St. Olaf (4). These figures have often been cited as portraying the Irish version of the kilt, but closer examination debunked this theory.

High crosses frequently depict religious subjects, but sometimes using what seems to be Irish garb. Here, the difficulty lies in discerning what exactly they depict. Years of weathering have eroded the stone of these relief carvings, blurring what details used to be present. Effigies, by contrast, normally top indoor tombs, safe from weathering. Sadly, the effigies currently known from Ireland all date to after the Norman Conquest.

That leaves the most important genre of Irish art: literature. The Irish generated an immense treasury of written material over the first millennium C.E., of which some has survived to today. The Irish learned writing with the coming of Christian missionaries in the late 300's CE and very early 400's CE, first using Latin, and then creating a written version of their own language (Old Irish). They also invented Ogham, a notation system for carving stones or slashing thin wooden rods; Ogham was primarily used for writing names and maker's marks, marking property boundaries, and occasionally writing down stories, poetry or records.

The majority of literate Irish were monastics, especially in the early period, but many of the records they kept (both in Old Irish and in Latin) were secular in nature (harvests, raids, deaths, famines, etc). As literacy spread, more such records emerged, and oral traditions were written down for the first time (or composed; some pseudohistories written in the 600-800's CE were likely invented by their writers). Laws, as well, were written down (although not codified).

These writings provide some of the most definite sources for Irish dress, since they were written about the Irish, by the Irish, using Irish words. Literary sources also provide cultural context for the articles of clothing, such as the existence of sumptuary laws, the status or profession of characters who wear certain styles of dress, or even simply gender. The only caution is that they must be taken in context and used as sources specifically for the time of the authors, not for the time of their subject material. For example, a story about an ancient hero might describe him wearing silk dyed purple, because the author was communicating the hero's grandeur to his audience, not trying to be historically accurate about the availability of silk or purple dye in ancient Ireland.

The other difficulty, of course, lies in translation. Not all words remained in use from Old Irish to Middle Irish, let alone to Modern Irish, particularly words for outdated clothing. Additionally, the Irish language has grammatical subtleties, so that a word will be spelled differently depending on its position in a sentence. Thankfully, the electronic Dictionary of Irish Language (5) is an increasingly thorough catalog of Old Irish words, citing where a particular word is found in the original writings, with a translation attempted based upon the various contexts. This dictionary/lexical survey has made studying Irish writings for evidence of clothes and customs significantly more accurate than ever before, and it continues to improve as the editors add to it. Its newest revision occurred in 2019.

The Norman Source: Giraldus

Cultural change came to Ireland with the conquest by the Anglo-Norman kings, beginning in 1169 in Leinster and finally taking the western provinces in the 1240's. In 1177, King Henry II of England gave the title, “Lord of Ireland”/Dominus Hiberniae (with theoretical rulership over the entire island) to his ten-year-old son Prince John Lackland. Prince John traveled to Ireland in 1185; in 1199, Richard the Lionhearted died and John became King of England and Ireland, but at the time there were still large portions of Ireland resistant to Norman forces. By 1250, half of the lords ruling in Ireland were Norman; half were still Irish, though they submitted to the King of England.

When Prince John visited his new lands in Ireland, his father sent him in company of a scholarly noble, Giraldus Cambrensis, who had just returned from a two-year trip around Ireland, learning about its climate, land, culture and people. The most commonly cited illuminations depicting Irish medieval dress come from two digitized copies of his book, Topographia Hibernica (6).

Gerald of Wales, as he is called in English, or Gerald de Barri, as he was christened in Wales, was born of Norman family and had great patriotic pride. He saw the Irish as proper subjects for conquest by his illustrious relations. When he came back to England after his second visit, Giraldus wrote a heavily biased work describing what he had seen in Ireland. This work, filled with some good information and some fanciful degradation of a populous he did not respect, circulated in Europe for centuries and set many standards of semi-scientific, encyclopedic writings. Perhaps he may be called the first English travel writer. The popularity of his work and the favor of the English crown encouraged him; Giraldus went on to write 16 more manuscripts, all in Latin.

Though Giraldus sketched with a bias, still, some key features of Irish dress come through in his illustrations. The basic shape and types of dress for men and women, in a variety of colors, and a generally long, free style of hair and beards, can be safely extrapolated from his depictions. Tunics and cloaks with hoods attached, not separate, are clearly visible. Tools and activities are shown, including playing music, writing, hunting and spinning. Giraldus emphasizes the Irish preference for the axe over other weaponry, painting several men with the Irish axe, but showing no other Irish weapons. This may be partly due to his propaganda goals of showing the Irish as inferior. For comparison, he shows his own Norman uncle, Maurice Fitzgerald, with an enormous sword on his belt in Expugnatio Hibernica.

It must be noted that the two illustrated copies of Topographia Hibernica are not equal in quality and were not produced by the same scribe. The British holding, Royal M.S. 13B VIII, ff 1r-34v, is the earliest copy known and was produced in Lincoln, probably in Gerald's presence, if not by his hand (7). The National Library of Ireland, in Dublin, holds NLI M.S. 700, produced in 1200 CE, which is a scribal copy of Giraldus' original edition. The marginal illustrations in NLI 700 are significantly inferior to Royal 13b, both in terms of the skill of the artist, and in terms of accuracy (the original illuminations have details such as a bridle on the horse, or anatomically appropriate breasts on the bearded lady, which the copying scribe has neglected). While both manuscripts are called by the same name, it helps to cite the origin for any close-up of the illuminations, to avoid confusion. Garb depicted in the original copy, Royal 13b, was at least seen and approved by the author, if he did not draw the illustrations himself, whereas the copying scribe in NLI 700 merely mimicked second-hand pictures.

Later period sources

The Norman Irish Parliament banned “Irish habits and customs” in 1297 (8). In 1366, the Statutes of Kilkenny banned intermarriage between English and Irish and required all Englishmen in Ireland to maintain the English styles and refrain from Irish apparel and customs (9). In 1466, the city of Dublin charged fines against all individuals—English or Irish—for even wearing a mantle in the Irish style when entering the city (10). Dissidents maintained their traditions, particularly in Western rural regions (farther from English influence), but these merely prompted further sumptuary laws to periodically emerge.

Meanwhile, “within the pale,” English and Continental styles prevailed. Here, the wearing of English dress proved one's loyalty to the crown (and accordingly associated one with the favor, trade and affluent connections of the foreign rulers). Effigies and manuscript illuminations show the nobles of Ireland wearing similar clothing to that found elsewhere in contemporary European countries, though often echoing slightly out-of-date styles.

In short, in the 14th and 15th centuries, the Irish mimicked the cotes, kirtles, barbettes, veils, houpelande, doublets, hoods, surcoats and overdresses of the more generic European styles. According to Luke Gernon in 1620, “the better sort [of Irish] are apparalled at all poynts like the English onely that they retain theyr mantle which is a garment not indecent. It differs nothing from a long cloke but in the fringe at the upper end which in could weather they wear over their heads for warmth" (11).

The clothing of the dissident, “wild” Irish of the rural countryside likely underwent similar changes in this period, but documenting their habits in any form between the 1180's and the 1500's is a serious challenge.

Disputed “Sources”

Some late-period illustrations have often been cited as evidence for earlier Irish garb. McClintock goes into great detail cataloging these:

In this inventory of pictorial evidence, McClintock clearly finds very few genuine depictions of Irish dress of the late period. He, logically, feels that those images where the artists were not even trying to portray Irish figures ought not be used to define Irish garb. Even those images often put forward as proof of the “saffron tunic” with enormous sleeves seem to be questionable. Too many of these images were crafted by those who either had never been to Ireland (foreigners trying to capture the aspect of the “barbaric Irish”) and had no first-hand knowledge of authentic Irish dress, or by artists who were actively hostile against the Irish and wished to present them in the worst possible light.

Only three of the 16th and 17th century images McClintock can find actually portray the Irish:

This lack of evidence for defining native Irish dress makes it difficult to say exactly what the Irish wore after the Norman Conquest, except for those who adopted English styles. Evidence for Irish nobles wearing Continental dress is abundant.

What is safe to say is that the illustrations listed above, so often held up as proof of Irish garb, should be considered extremely suspect or outright bogus. Consequently, those wishing to recreate late-period (post-Norman Conquest) Irish garb should focus more upon tangible finds, such as the Shinrone Gown, the Moy Bog Dress, the Co. Sligo bog men's attire and other extant clothing in museums today.

To continue reading about early medieval Irish garb, see Irish Garb: Part 2.

Sources:

1) Raftery, Barry. “Iron Age Ireland.” A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Oxford University Press, 2005. p. 145

2) Heckett, Elizabeth Wincott. Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin: Medieval Dublin excavations, 1962-81, Medieval Dublin Excavations. Royal Irish Academy, 2003.

3) St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 51: Irish Evangelary from St. Gall (Quatuor evangelia) (http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0051).

4) Wilson, David. "An Early Representation of St Olaf." Medieval Literature and Civilization. A&C Black, 2014. p. 141-145

5) eDIL: Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, edited by Gregory Toner, Máire Ni Mhaonaigh, Sharon Arbuthnot, Marie-Luise Theuerkauf and Dagmar Wodtko. <www.dil.ie> Updated 2019.

6) Giraldus Cambrensis. Topographia Hiberniae. 1188. Royal MS 13 B VIII f.1r-34v digitized by the British Library.

7) Brown, Michelle. “Marvels of the West: Giraldus Cambrensis and the Role of the Author in the Development of Marginal Illustration.” Decoration and Illustration in Medieval English Manuscripts, ed. A.S.G. Edwards, in English Manuscript Studies 1100-1700, Vol. 10. 2002. p. 47

8) State, Paul F. A Brief History of Ireland. Infobase Publishing, 2009. p. 74

9) O'Connor, Thomas Power. Gladstone, Parnell, and the great Irish struggle. Edgewood Publishing Co., Philadelphia, PA, 1886.

10) Dunlevy, Mairead. Dress in Ireland: A History. Collins Press, 1989. p. 54

11) McClintock, Henry Foster. Handbook on the Traditional Old Irish Dress. 1958. p. 41

Background

During the prehistoric period in Ireland, the insular Irish developed unusual laws, clothing and habits, relatively independently from the Continental trends of the time. Thanks to their island status, their material culture seems to have continued with few changes for many centuries, from the Iron Age onward. According to Barry Raftery, the Irish had a tendency to thoroughly assimilate anything new into their existing culture, art, and economy, without themselves being much changed by its adoption: “this illustrates well the recurring conundrum of Irish prehistory. Here we have something that is totally new in the country, yet rendered in a form that is different in detail from anything in the area of presumed origin.” (1) Thus, the Irish managed to hold on to a pastoral economy of grain, pig, and most importantly, cattle-raising, with a dispersed population on decentralized family holdings and a tribal style of chiefs and kings, in a very stable pattern of dwelling, economy and political structure, through a period of growth and increasing wealth from 200 CE to around 1200 CE.

Christianity reached the island in the 400's CE, bringing writing, ecclesiastic hierarchy, and saintly cults, but it appears to have altered little in terms of secular garb and lifestyles. Literacy spread, and the Church secured a strong political power, but material culture seems to have remained stable.

The Viking incursions in the 800's CE likewise seem to have changed little of the local apparel (except, perhaps, the brief use of the warp-weighted loom). Although the Viking towns did create the first urban environments in Ireland, with subsequent market economy increasing over the years, and trade certainly improved during this period, life for the average Irish farmer would likely have been much as it had been centuries earlier.

The Norman invasion and conquest of Ireland, however, forced dramatic changes in economy, property transfer, politics and, eventually, dress. As a conquered people of a colonial power, the Irish found their ways gradually suppressed as their resources were exploited for foreign profit. Thus the traditional Irish ways gave way (not without resistance) by the mid-1300's CE, and Irish dress lost permanently most of those aspects which had previously made it unique.

Unfortunately, centuries of suppression under English rule destroyed many records that might have provided details about the ancient Irish culture. Furthermore, Victorian “Celtophile” writings (and the eugenics movement that influenced early historians) sadly muddied the waters (see Insular, not Celtic). This resulted in popular notions of early Irish dress that were tragically inaccurate, and even today linger as a challenge for modern reenactors to overcome.

Happily, thanks to the recent efforts of archaeologists, translators and archivists, a wealth of new information is currently pouring out of Ireland—making research into Irish material culture suddenly more feasible. Modern efforts center on correcting errors, increasing the accuracy of translations and improving access to new archaeological discoveries.

Commonly Cited Sources

Much of the information publicly available documenting Irish clothing depends on a few early (mostly 19th century) translations of Brehon Law and the Irish Annals, along with a few woodcut images from the late 1500's CE. Unfortunately, early errors have been cited, repeated and depended upon for so many decades that it can be difficult to sift through them for correct information.

1. The earliest modern historical attempt to understand old Irish dress comes from Eugene O'Curry's lectures, published posthumously in Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish (1873), and his work with John O'Donovan and a team funded by the British Government for the task of translating ancient Irish law. Sadly, due to misinterpreted language and some cultural bias, these produced many false understandings of Irish culture and custom. This is not to disparage the effort O'Curry put into the massive task of translating thousands of pages of ancient Irish records from aging manuscripts.

However, O'Curry specialized in Middle and Early Modern Irish language, not Old Irish, and could not grasp the subtleties and technicalities represented in these legal works. In one often-cited example, O'Curry mistranslates “leine” (the Irish word for a linen tunic) as “a kilt,” and he goes on to defend his belief in Irish kilts, in depth, ignoring any indications to the contrary (such as that some lente having hoods attached to them, which would be hard to imagine on a waist-to-knee kilt).

2. Patrick Weston Joyce, author of Social History of Ireland (1903) and A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland (1906), referenced O'Curry for many of his sources and adopted his belief in the mistranslated or misinterpreted concepts, such as the kilt. Thankfully, not all of his citations depended on O'Curry's work, and not all of his information was wrong; Joyce's books still serve as a useful overview of artifacts and finds from Ireland. One major problem in his work was his routine neglect of historical context; he cites wood-cuttings from the 1500's CE alongside poetry from the 700's CE and archaeological finds from the Bronze Age, trying to force them all to fit together into one unaltered culture when many centuries of major social change segregate their contexts. Both Joyce and O'Curry helped shape modern scholastic interest in ancient Ireland, but using or citing their findings and conclusions requires caution. Any works citing them without other, corroborating works (ones which do not also depend on either Joyce or O'Curry for their information) should be tested for validity by extensive fact-checking.

3. Henry Foster McClintock provides the next major source for analyzing Irish garb. In 1958, his Handbook on the Traditional Old Irish Dress expanded upon the initial work he had put forward in his 1943 book, Old Irish and Highland Dress. Though more research, images, manuscripts and archaeological finds have become available since McClintock's time, these books still encompass much of the known Irish customs in clothing, and provide a useful overview. McClintock had a humble and pragmatic perspective on documentation—he recognized his own lack of knowledge of the ancient Irish language, which he points out in his first pages is not the same as more modern varieties of Gaelic, and therefore refrains from using much of the text then available for documenting his garb research (saying that he cannot verify the translations of the words involved). This book provides an excellent first step for anyone who wishes to study Irish garb—though it is not the final word on the subject, as current archeology continues to uncover new information.

4. Mairead Dunlevy published a more complete overview of Irish clothing through the ages in her book, Dress in Ireland (1989, republished in 2000). Dunlevy's interests in dress included modern designers, Irish lace-making history, poplin and other 18th through 20th century fabric uses, jewelry, glassware, etc. She curated at the National Museum of Ireland for many years, and her research had a solid foundation on actual finds housed in the Museum. However, her analyses lack much detail that would help in reconstructing these garments. She clearly prefers the more recent ages of fashion, and gives only a scant overview of earlier garb. Her single chapter on pre-1300's CE Irish dress tries to encompass everything from prehistoric and Iron Age clothing to garb in the Norman conquest, in only a few pages. The synopsis of garb from such an expansive time period is necessarily broad and generalized, with very few hints on how such clothing could be reproduced. She examines only one of the manuscripts available of Topographia Hibernica—an inferior copy—for her source on Irish clothing during the Norman period. Thus her information for Irish garb prior to the 1300's CE is limited. Still, her book provides an excellent introduction into Irish clothing trends, with a bibliography to point the way to further research.

Many other works exist studying the Irish art, metalwork, history and lore; for instance, Karl S. Bottigheimer's work Ireland and the Irish: a short history covers much of the historic trends in population and politics in Ireland. A.T. Lucas's 1956 study of “Footwear in Ireland” examines the evidence then available for how the Irish made their shoes. However, many of these works are now out of date, as new information has come to light since their publication, so their conclusions must be read with that caution in mind.

Additionally, early Irish archaeological studies rarely mentioned textiles or leather, being more extensively interested in treasure and weapons. Of course, this stems in part from how well metals and gems withstand the Irish climate, unlike textiles. In most cool, damp northwestern European climates, “fibers made from animal protein can survive in good order while cellulose vegetable fibers cannot” (2). This makes locating extant pieces difficult and leads to the mistaken assumption that northerners only wore wool—an assumption provably wrong, but easy to make if one acknowledges only extant pieces of garb, without literary or artistic context.

Extant Pieces

Bog bodies and bog finds, where the cool, acidic, anaerobic environment tans and preserves skins, leathers and sometimes wood (though usually not bone), sometimes include textiles. The Moy Bog dress, for example, survives in amazing condition despite its age (ca.1400 CE) thanks to the bog where it was abandoned. Sadly, most of the existing bog textiles come from pre-industrialized peat mining, where humans with shovels encountered bodies or other articles embedded in the peat and stopped work to investigate. Today, mining machines used for milling the peat often massively damage or outright destroy the finds before operators notice their presence. This leads to a sad conundrum; older finds which were uncovered intact and relatively undisturbed were often poorly preserved after their disinterment, frequently leading to their disintegration or at least decay. Many of the treatments applied to keep them whole for display have ruined the chances of chemical analyses and dating. Meanwhile, modern methods for preservation would allow such finds to be kept in good condition and examined more completely by textile experts, etc.—but few finds now come to light, as modern machines shred the artifacts. Those few textile finds retrieved from bogs are often difficult to analyze, thanks in part to the attempted preservation techniques, and in part to the chemical changes inherent in bog immersion (red and brown coloration, etc). Skin products reclaimed from bogs are invariably tanned by the tannins in bog water, and so the tanning methods (or lack thereof) of the shoes, bags, etc cannot be determined.

Outside of bogs, textile and leather finds often come from waterlogged sites (shipwrecks, crannogs, etc), indoor storage (grandmother's old trunk of heirlooms in the attic, etc.), or else from salt mines, deserts and glaciers. In Ireland, most indoor treasures were deliberately destroyed by conquerors who felt the need to suppress Irish nationalism during many centuries of foreign rule. The Irish climate provides neither deserts nor glaciers, and documenting textiles found in Continental salt mines as belonging to Ireland or people of Irish origin is exceedingly difficult. Some fragments of textiles have been luckily preserved in graves and the dirt of early settlements. Archaeological digs since the economic boom called the Irish Tiger have been more comprehensive in documenting these finds and preserving them for further examination. However, most of what is left comes in tiny scrap form and rarely gets much publicity outside of the archaeological community.

Primary Sources

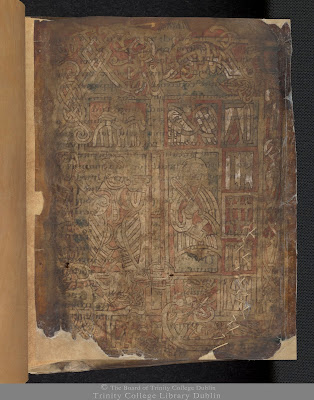

|

| IE TCD MS 56 f.1r |

Beyond extant remnants, primary sources for Irish garb include art and literature of the period. Manuscripts sometimes include illuminations with humans depicted in Irish garb, with various degrees of stylized artistic rendering. Relevant manuscripts include some from Irish monasteries (such as the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow, and the Irish Evangelary from St. Gall (3)). There are also manuscripts by contemporary authors in Continental Europe who wrote down hearsay about the Irish (the least reliable of period sources). These illuminations and written depictions range from relatively realistic to clearly abstract or third-hand, and can be cited for garb documentation only with awareness of the limitations of the medium and the bias of the authors involved.

|

| Book of Kells, f.89r |

Relief carvings on statues, effigies, crosses, reliquaries, church walls, etc. can also offer clues into the clothing experiences and expectations of the artists creating them. Where details can be made out, the garb portrayed can inform the researcher's understanding of what the artist may have been accustomed to in local dress. However, this again must be approached with caution. Many such carvings have religious context and were meant to portray figures from Biblical stories or hagiographies, sometimes with deliberately foreign garb or styles of artwork. For example, according to David Wilson, the bronze relief figures on the Shrine of St. Manchan represent the Irish interpretation of Scandinavian artwork (the Irish Urnes style, early 1100's CE) and portray at least one Scandinavian saint, St. Olaf (4). These figures have often been cited as portraying the Irish version of the kilt, but closer examination debunked this theory.

|

| Shrine of St. Manchan in the Irish Urnes style (hybrid Scandinavian Irish art) |

High crosses frequently depict religious subjects, but sometimes using what seems to be Irish garb. Here, the difficulty lies in discerning what exactly they depict. Years of weathering have eroded the stone of these relief carvings, blurring what details used to be present. Effigies, by contrast, normally top indoor tombs, safe from weathering. Sadly, the effigies currently known from Ireland all date to after the Norman Conquest.

|

| Clonmacnois Scripture Cross: two soldiers |

That leaves the most important genre of Irish art: literature. The Irish generated an immense treasury of written material over the first millennium C.E., of which some has survived to today. The Irish learned writing with the coming of Christian missionaries in the late 300's CE and very early 400's CE, first using Latin, and then creating a written version of their own language (Old Irish). They also invented Ogham, a notation system for carving stones or slashing thin wooden rods; Ogham was primarily used for writing names and maker's marks, marking property boundaries, and occasionally writing down stories, poetry or records.

The majority of literate Irish were monastics, especially in the early period, but many of the records they kept (both in Old Irish and in Latin) were secular in nature (harvests, raids, deaths, famines, etc). As literacy spread, more such records emerged, and oral traditions were written down for the first time (or composed; some pseudohistories written in the 600-800's CE were likely invented by their writers). Laws, as well, were written down (although not codified).

These writings provide some of the most definite sources for Irish dress, since they were written about the Irish, by the Irish, using Irish words. Literary sources also provide cultural context for the articles of clothing, such as the existence of sumptuary laws, the status or profession of characters who wear certain styles of dress, or even simply gender. The only caution is that they must be taken in context and used as sources specifically for the time of the authors, not for the time of their subject material. For example, a story about an ancient hero might describe him wearing silk dyed purple, because the author was communicating the hero's grandeur to his audience, not trying to be historically accurate about the availability of silk or purple dye in ancient Ireland.

The other difficulty, of course, lies in translation. Not all words remained in use from Old Irish to Middle Irish, let alone to Modern Irish, particularly words for outdated clothing. Additionally, the Irish language has grammatical subtleties, so that a word will be spelled differently depending on its position in a sentence. Thankfully, the electronic Dictionary of Irish Language (5) is an increasingly thorough catalog of Old Irish words, citing where a particular word is found in the original writings, with a translation attempted based upon the various contexts. This dictionary/lexical survey has made studying Irish writings for evidence of clothes and customs significantly more accurate than ever before, and it continues to improve as the editors add to it. Its newest revision occurred in 2019.

The Norman Source: Giraldus

|

| MS 13B VII f.29r |

Cultural change came to Ireland with the conquest by the Anglo-Norman kings, beginning in 1169 in Leinster and finally taking the western provinces in the 1240's. In 1177, King Henry II of England gave the title, “Lord of Ireland”/Dominus Hiberniae (with theoretical rulership over the entire island) to his ten-year-old son Prince John Lackland. Prince John traveled to Ireland in 1185; in 1199, Richard the Lionhearted died and John became King of England and Ireland, but at the time there were still large portions of Ireland resistant to Norman forces. By 1250, half of the lords ruling in Ireland were Norman; half were still Irish, though they submitted to the King of England.

When Prince John visited his new lands in Ireland, his father sent him in company of a scholarly noble, Giraldus Cambrensis, who had just returned from a two-year trip around Ireland, learning about its climate, land, culture and people. The most commonly cited illuminations depicting Irish medieval dress come from two digitized copies of his book, Topographia Hibernica (6).

Gerald of Wales, as he is called in English, or Gerald de Barri, as he was christened in Wales, was born of Norman family and had great patriotic pride. He saw the Irish as proper subjects for conquest by his illustrious relations. When he came back to England after his second visit, Giraldus wrote a heavily biased work describing what he had seen in Ireland. This work, filled with some good information and some fanciful degradation of a populous he did not respect, circulated in Europe for centuries and set many standards of semi-scientific, encyclopedic writings. Perhaps he may be called the first English travel writer. The popularity of his work and the favor of the English crown encouraged him; Giraldus went on to write 16 more manuscripts, all in Latin.

|

| MS 13B VIII f.28r Irish men with axes |

Though Giraldus sketched with a bias, still, some key features of Irish dress come through in his illustrations. The basic shape and types of dress for men and women, in a variety of colors, and a generally long, free style of hair and beards, can be safely extrapolated from his depictions. Tunics and cloaks with hoods attached, not separate, are clearly visible. Tools and activities are shown, including playing music, writing, hunting and spinning. Giraldus emphasizes the Irish preference for the axe over other weaponry, painting several men with the Irish axe, but showing no other Irish weapons. This may be partly due to his propaganda goals of showing the Irish as inferior. For comparison, he shows his own Norman uncle, Maurice Fitzgerald, with an enormous sword on his belt in Expugnatio Hibernica.

|

| NLI MS 700 f.77v Maurice Fitzgerald the Norman. |

|

| MS 13B VIII f.30v Irish cripple |

It must be noted that the two illustrated copies of Topographia Hibernica are not equal in quality and were not produced by the same scribe. The British holding, Royal M.S. 13B VIII, ff 1r-34v, is the earliest copy known and was produced in Lincoln, probably in Gerald's presence, if not by his hand (7). The National Library of Ireland, in Dublin, holds NLI M.S. 700, produced in 1200 CE, which is a scribal copy of Giraldus' original edition. The marginal illustrations in NLI 700 are significantly inferior to Royal 13b, both in terms of the skill of the artist, and in terms of accuracy (the original illuminations have details such as a bridle on the horse, or anatomically appropriate breasts on the bearded lady, which the copying scribe has neglected). While both manuscripts are called by the same name, it helps to cite the origin for any close-up of the illuminations, to avoid confusion. Garb depicted in the original copy, Royal 13b, was at least seen and approved by the author, if he did not draw the illustrations himself, whereas the copying scribe in NLI 700 merely mimicked second-hand pictures.

|

|

Later period sources

The Norman Irish Parliament banned “Irish habits and customs” in 1297 (8). In 1366, the Statutes of Kilkenny banned intermarriage between English and Irish and required all Englishmen in Ireland to maintain the English styles and refrain from Irish apparel and customs (9). In 1466, the city of Dublin charged fines against all individuals—English or Irish—for even wearing a mantle in the Irish style when entering the city (10). Dissidents maintained their traditions, particularly in Western rural regions (farther from English influence), but these merely prompted further sumptuary laws to periodically emerge.

Meanwhile, “within the pale,” English and Continental styles prevailed. Here, the wearing of English dress proved one's loyalty to the crown (and accordingly associated one with the favor, trade and affluent connections of the foreign rulers). Effigies and manuscript illuminations show the nobles of Ireland wearing similar clothing to that found elsewhere in contemporary European countries, though often echoing slightly out-of-date styles.

In short, in the 14th and 15th centuries, the Irish mimicked the cotes, kirtles, barbettes, veils, houpelande, doublets, hoods, surcoats and overdresses of the more generic European styles. According to Luke Gernon in 1620, “the better sort [of Irish] are apparalled at all poynts like the English onely that they retain theyr mantle which is a garment not indecent. It differs nothing from a long cloke but in the fringe at the upper end which in could weather they wear over their heads for warmth" (11).

The clothing of the dissident, “wild” Irish of the rural countryside likely underwent similar changes in this period, but documenting their habits in any form between the 1180's and the 1500's is a serious challenge.

Disputed “Sources”

Some late-period illustrations have often been cited as evidence for earlier Irish garb. McClintock goes into great detail cataloging these:

- one sketch by Albrecht Dürer (who never visited Ireland at all) from 1521

- one wood-cutting made by an unknown artist in England perhaps around 1550 (possibly based upon a group of captured soldiers brought to England from Ireland for display)

- one water-color painting by Lucas de Heere, a Flemish artist who lived several years in England, but never visited Ireland; he relied on descriptions given to him by the English

- twelve wood-cuttings from an author named Derrick in 1581, who may have served as a soldier in Ireland under Sir Henry Sidney. (His book disparages the Irish in every manner possible, sometimes very coarsely, according to McClintock—and indeed, his images include Irish soldiers publicly defecating at the feast table, burning village homes and being defeated in battle against the English.)

- two battle drawings by English soldier John Thomas in the 1590's with figures wearing trews and jackets (McClintock calls the drawings “schoolboy-like,” too small-scale to be useful)

- one colored drawing on velum depicting the 1599 seizure of the Earl of Ormonde by Irish treachery (the figures are very small and lack detail; the Irish wear trews in this image, with padded jackets, conical helmets and square sword-scabbards on their belts, but little more can be discerned from it)

- one battle drawing reproduced in Hibernica Pacata in 1603 portraying the fighting at Kinsale, again with small figures wearing trews and jackets

- six “Irish” figures in marginalia on Speede's Map of Ireland from 1610; McClintock points out that the “Wild Irish” shown here are merely “adaptations of a French print of Scottish Highlanders published about 60 years earlier... and must therefore be disregarded” (11)

- graffiti/wall painting on the church wall of Holy Cross Abbey, Co. Tipperary, from the early 1600's showing a hunting scene with men using English longbows and hounds to pursue a stag (McClintock comments that the secular artwork probably came from the garrison that occupied the abbey during its suppression, when the monks were evicted from their monastery, and that the figures portrayed may be genuinely Irish, or may be wearing an English style of the period)

- graffiti/wall painting on the church wall of Abbey Knockmoy, Co. Galway, showing the legend of three dead kings and three living kings as well as the Martyrdom of St. Christopher, with some six figures dressed in Continental styles (McClintock refutes Joyce's claim that they wear Irish kilts, pointing out the English shoes and that the clothing shown is identical to that in many English, Flemish, French and Italian paintings of the time—which, when paired with themes that were more popular on the Continent, suggests again that a foreign artist created the graffiti).

In this inventory of pictorial evidence, McClintock clearly finds very few genuine depictions of Irish dress of the late period. He, logically, feels that those images where the artists were not even trying to portray Irish figures ought not be used to define Irish garb. Even those images often put forward as proof of the “saffron tunic” with enormous sleeves seem to be questionable. Too many of these images were crafted by those who either had never been to Ireland (foreigners trying to capture the aspect of the “barbaric Irish”) and had no first-hand knowledge of authentic Irish dress, or by artists who were actively hostile against the Irish and wished to present them in the worst possible light.

Only three of the 16th and 17th century images McClintock can find actually portray the Irish:

- a crude wood carving (which McClintock provides a sketch of, based upon a rubbing of it; presumably he did not get to see the original) showing an Irish piper wearing a tunic with vertical lines (perhaps stripes, perhaps pleats or folds) and trews—but McClintock provides no date for this carving from Woodstock Castle, Co Kilkenny

- an illuminated manuscript (Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. C.32) from the early 1500's (though the marginalia may be much more recent) showing an Irish piper with tightly fitted sleeves and trews, with voluminous skirts of some sort, though the artist had difficulty with perspective and included many fanciful elements in other marginalia

- five engraved figures on the cover of a book dating from around 1620, crudely drawn, with dancing men wearing trews and jackets

This lack of evidence for defining native Irish dress makes it difficult to say exactly what the Irish wore after the Norman Conquest, except for those who adopted English styles. Evidence for Irish nobles wearing Continental dress is abundant.

What is safe to say is that the illustrations listed above, so often held up as proof of Irish garb, should be considered extremely suspect or outright bogus. Consequently, those wishing to recreate late-period (post-Norman Conquest) Irish garb should focus more upon tangible finds, such as the Shinrone Gown, the Moy Bog Dress, the Co. Sligo bog men's attire and other extant clothing in museums today.

To continue reading about early medieval Irish garb, see Irish Garb: Part 2.

Sources:

1) Raftery, Barry. “Iron Age Ireland.” A New History of Ireland: Prehistoric and Early Ireland. Oxford University Press, 2005. p. 145

2) Heckett, Elizabeth Wincott. Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin: Medieval Dublin excavations, 1962-81, Medieval Dublin Excavations. Royal Irish Academy, 2003.

3) St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 51: Irish Evangelary from St. Gall (Quatuor evangelia) (http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0051).

4) Wilson, David. "An Early Representation of St Olaf." Medieval Literature and Civilization. A&C Black, 2014. p. 141-145

5) eDIL: Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language, edited by Gregory Toner, Máire Ni Mhaonaigh, Sharon Arbuthnot, Marie-Luise Theuerkauf and Dagmar Wodtko. <www.dil.ie> Updated 2019.

6) Giraldus Cambrensis. Topographia Hiberniae. 1188. Royal MS 13 B VIII f.1r-34v digitized by the British Library.

7) Brown, Michelle. “Marvels of the West: Giraldus Cambrensis and the Role of the Author in the Development of Marginal Illustration.” Decoration and Illustration in Medieval English Manuscripts, ed. A.S.G. Edwards, in English Manuscript Studies 1100-1700, Vol. 10. 2002. p. 47

8) State, Paul F. A Brief History of Ireland. Infobase Publishing, 2009. p. 74

9) O'Connor, Thomas Power. Gladstone, Parnell, and the great Irish struggle. Edgewood Publishing Co., Philadelphia, PA, 1886.

10) Dunlevy, Mairead. Dress in Ireland: A History. Collins Press, 1989. p. 54

11) McClintock, Henry Foster. Handbook on the Traditional Old Irish Dress. 1958. p. 41

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions and suggestions for further research are welcome. No selling, no trolling, and back up any critique with modern scholarly sources. Comments that do not meet these criteria will be discarded.