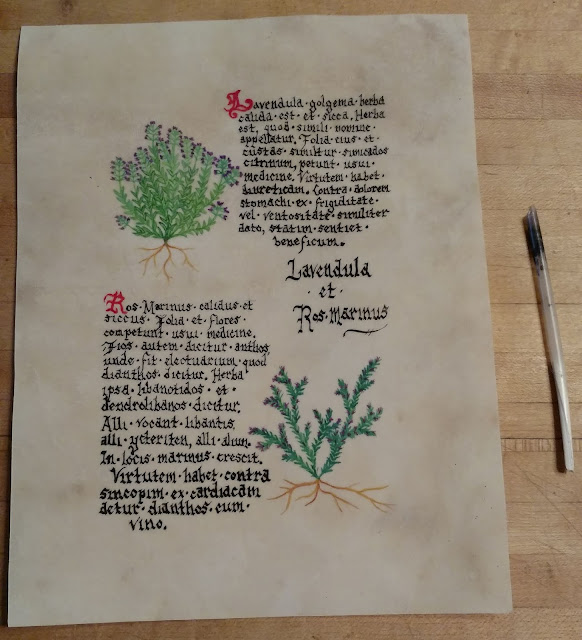

Parchment Part 1

Parchment: Medieval Availability & Use Deerskin parchment, with a duck feather quill pen. In the medieval period, scribes across Europe relied upon animal skin for their painting/writing/book-making medium. Paper existed (such as papyrus, in northern Africa, hemp and mulberry paper in Asia) but in the colder, wetter climate of northern Europe, animal skin was comparatively abundant, affordable, more durable and easier to make. Skins were a constant natural byproduct of butchering livestock for meat. Flat, stretched rawhide, called parchment or vellum (depending on thinness & quality), could be written upon with char pencil, chalk, ink or paint; it could be dyed special colors and cut into useful shapes (rectangles, hearts, etc), and it would last for centuries, so long as it was kept dry. It was also far more reusable than papyrus. Cow, goat, sheep and deer skin could all be made into parchment without too much labor investment, and the skin from the young animals (cal...