Charcoal Pits (Charcoal 3)

Charcoal Pits

Creating charcoal begins with preparing a burn site. With the mound method, this means scraping clean a level, above-ground surface, cleared to prevent the spread of fire. This can include building earthwork sides or half-walls to reduce the labor of enclosing the burn pile. However, a safer and more certain method is to dig a trench or pit hearth, and to conduct the charcoal burn below grade.

Burning within a sheltering bank of earth provides two major benefits, compared with open mounds:

1) It reduces the dirt-shoveling labor involved in repeated burns, so long as the same site is used each time. Rather than having to cover an entire mound with dirt every time a charcoal mound is fired, the charcoal burner leaves the earthen sides permanently in place. He only needs to cover the top of the burn pile, and likewise, needs only to uncover the top of the burn pile, each time the charcoal pit is used. He can also design air control features (vents, chimneys) into the permanent structure of the pit, rather than having to re-do the effort for each burn. These permanent vents can be designed to close or be fully blocked by reusable covers or blocks.

2) The solid insulation of the earthen walls prevents the risk of cracks and dirt-slippage in the sides of the mound. Cracks allow unwanted air into the smothered charcoal burn, causing it to ignite and consume the fuelwood, instead of converting it into carbon. A pit shape, with solid, vertically sloped walls, also encourages the dirt cover to settle continuously down onto the pile—thus preventing bubbles of explosive woodgas from building up and exploding. This erases the need for laborers to tamp down the soil (at great risk to themselves).

The pit kiln, however, is not a mobile infrastructure. If the charcoal burner denudes the forest in his efforts to produce more charcoal, then he will soon have no wood near his kiln and will have to relocate, and dig a new kiln. Since a large part of the labor saved by using a pit kiln comes from not having to dig it again, this style of charcoal production is not as efficient for a culture that practices nomadic deforestation. Indeed, the pit kiln is only a labor-saving investment if the charcoal burner plans to reuse it repeatedly, especially if he can maintain a forest resource nearby to continually harvest for fuel wood. Happily, people in northern Europe had already invented just such a forest management practice in the Bronze Age, before charcoal production became an industry. By coppicing the hardwoods to produce fast-growing, consistent diameter, straight poles that were easier to cut for fuel, the charcoal burner could guarantee a constant harvest of material for his pit kiln.

Indeed, the archaeological evidence confirms that in places like Ireland, where pit kilns first became popular, coppicing was the primary method to supply them with fuelwood. The vast majority of charcoal found in the pit kilns of Ireland is oak wood, harvested when it was between 15 to 25 years old, most frequently about 10cm (about 4 inches) in diameter (1). This consistency, and the very young age of the poles thus harvested, and the consistency of diameter, all provide very strong evidence for the use of coppice wood in these pit kilns.

The method for producing charcoal in a pit therefore begins with the construction of a pit for the purpose. Interestingly, charcoal production pits (called, “pit kilns”) appear to have a limiting range of size. Whereas the mound method gains in efficiency as it gets larger, until it may give yields as high as 25%, the pit kiln starts to lose efficiency if it is made too large. The ideal size for a pit kiln is scaled more appropriately for homestead or village use, often as small as 1.4m L x 0.9m W x 0.5m D (2), while mounds may grow to as much as 12m (40 feet) in diameter. At this small size, a pit kiln averages 22%-30% efficiency, but it drops quickly when scaled even to just 6 meters wide (3).

Method:

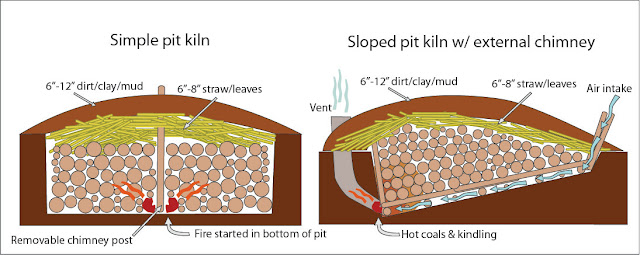

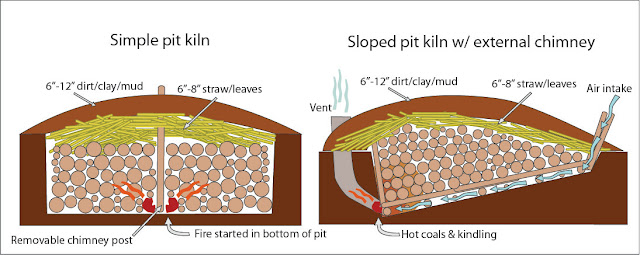

The pit can be as simple as an excavated rectangle or round hole, roughly a meter or two long, one meter wide and half a meter deep. This simple style requires the burner to light a fire in the bottom first, and get the pit hot with a layer of red coals in the bottom. Then he sets the chimney logs in place in the center, quickly stacks the fuel wood on the hot coals, covers them with green mulch and covers that with dirt. Then he pulls the chimney logs out to vent the pile, which smokes and steams until the moisture is gone and no more steam comes out. At that point, he closes the chimney holes with more dirt and monitors the smothered pile. When it completely cools, he digs off the dirt, then the charred mulch, and finally digs out the charred fuel wood. This method is still in practice today around the world.

An improved pit design features a sloped bottom, with the same basic dimensions; the slope runs from one long-side to the other long-side. Thus, one 1m long side will be half a meter deep, but the other 1m long side will only be slightly below grade—and it can be tapered out to make the slope reach ground level, if convenient for the digger. This design includes vent logs. The vent logs should be young saplings that are still green, so that they resist burning, and they should be laid in pairs to provide for air draft in the gap between them. The chimney logs should stand upright in the deep end of the pit, and the vent log pairs should bracket them, and be laid along the slope to the shallow end, sticking out of the pit. The charcoal burner should set these in place first, and then lay kindling around them as a base layer in the pit before stacking the fuel wood across the vent logs. He then covers the stack with green mulch and dirt, except he leaves a small access gap at the shallow end to reach the kindling. Then he shoves hot coals into the kindling at these gaps, lighting the fire and getting it hot, and pulling the chimney logs out to start the draft circulating, before finishing covering the pile. Hot coals can also be dropped down the chimney holes, if needed.

When the pile is steaming and smoke is emerging from the chimney holes, the burn is successfully lit. The charcoal burner then waits until the steam clears and only smoke shows, and smothers the vents and chimneys. Then he waits until it cools completely, and digs it out.

A final method of improving the pit design requires digging a permanent chimney vent, sloped upward from the deep end of the pit, opposite the slope of the pit itself. Hot coals are dropped down the chimney to light the kindling laid in the bottom of the pit, after the fuel stack is built and covered. Vent logs are still required but no chimney logs are needed, and a permanent cover (such as a flat rock) can close the chimney.

Pit kilns of the simple rectangle and the sloped types are, for instance, found in England and Ireland, such as the rectangular kiln found at Russagh 4, County Offaly. This kiln, dated between 994-1153 CE, and a round pit kiln nearby, were used to produce oak charcoal from a local coppice wood. The Russagh 4 example easily generates 30 kg or more of charcoal per small batch, enough to smelt iron in a small local bloomery, according to experimental reconstructions of this kiln (2).

Toward the end of the medieval period, Europeans also began experimenting with even more efficient methods to produce charcoal, using enclosed masonry structures called retorts (inspired by the shapes of lime kilns and pitch kilns). By the early 1600's, stone, sod, clay and brick beehive structures had replaced the traditional methods for charcoal production in Europe and the colonies. Examples of the new charcoal retorts include a red brick retort in Ireland (Russagh 2, Offaly), that saw use into the 1600's (4).

Sources:

1) Warren, Graeme; McDermott, Conor; O'Donnell, Lorna and Sands, Rob. “Recent Excavations of Charcoal Production Platforms in the Glendalough Valley, Co. Wicklow.” NUI, The Journal of Irish Archaeology, 21 : 85-112, 2012.

2) Dolan, Brian. “Traditional Charcoal Making Experiment.” Leaflet. 2010. charcoal.seandalaiocht.com

3) “Simple Technologies for Charcoal Making.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO Forestry, Paper 41, 1983.

4) “Post-medieval burnt spread and pit.” 2007: AD39 Russagh 2. Database of Irish Excavation Reports.

The pit can be as simple as an excavated rectangle or round hole, roughly a meter or two long, one meter wide and half a meter deep. This simple style requires the burner to light a fire in the bottom first, and get the pit hot with a layer of red coals in the bottom. Then he sets the chimney logs in place in the center, quickly stacks the fuel wood on the hot coals, covers them with green mulch and covers that with dirt. Then he pulls the chimney logs out to vent the pile, which smokes and steams until the moisture is gone and no more steam comes out. At that point, he closes the chimney holes with more dirt and monitors the smothered pile. When it completely cools, he digs off the dirt, then the charred mulch, and finally digs out the charred fuel wood. This method is still in practice today around the world.

An improved pit design features a sloped bottom, with the same basic dimensions; the slope runs from one long-side to the other long-side. Thus, one 1m long side will be half a meter deep, but the other 1m long side will only be slightly below grade—and it can be tapered out to make the slope reach ground level, if convenient for the digger. This design includes vent logs. The vent logs should be young saplings that are still green, so that they resist burning, and they should be laid in pairs to provide for air draft in the gap between them. The chimney logs should stand upright in the deep end of the pit, and the vent log pairs should bracket them, and be laid along the slope to the shallow end, sticking out of the pit. The charcoal burner should set these in place first, and then lay kindling around them as a base layer in the pit before stacking the fuel wood across the vent logs. He then covers the stack with green mulch and dirt, except he leaves a small access gap at the shallow end to reach the kindling. Then he shoves hot coals into the kindling at these gaps, lighting the fire and getting it hot, and pulling the chimney logs out to start the draft circulating, before finishing covering the pile. Hot coals can also be dropped down the chimney holes, if needed.

When the pile is steaming and smoke is emerging from the chimney holes, the burn is successfully lit. The charcoal burner then waits until the steam clears and only smoke shows, and smothers the vents and chimneys. Then he waits until it cools completely, and digs it out.

A final method of improving the pit design requires digging a permanent chimney vent, sloped upward from the deep end of the pit, opposite the slope of the pit itself. Hot coals are dropped down the chimney to light the kindling laid in the bottom of the pit, after the fuel stack is built and covered. Vent logs are still required but no chimney logs are needed, and a permanent cover (such as a flat rock) can close the chimney.

Pit kilns of the simple rectangle and the sloped types are, for instance, found in England and Ireland, such as the rectangular kiln found at Russagh 4, County Offaly. This kiln, dated between 994-1153 CE, and a round pit kiln nearby, were used to produce oak charcoal from a local coppice wood. The Russagh 4 example easily generates 30 kg or more of charcoal per small batch, enough to smelt iron in a small local bloomery, according to experimental reconstructions of this kiln (2).

Toward the end of the medieval period, Europeans also began experimenting with even more efficient methods to produce charcoal, using enclosed masonry structures called retorts (inspired by the shapes of lime kilns and pitch kilns). By the early 1600's, stone, sod, clay and brick beehive structures had replaced the traditional methods for charcoal production in Europe and the colonies. Examples of the new charcoal retorts include a red brick retort in Ireland (Russagh 2, Offaly), that saw use into the 1600's (4).

Sources:

1) Warren, Graeme; McDermott, Conor; O'Donnell, Lorna and Sands, Rob. “Recent Excavations of Charcoal Production Platforms in the Glendalough Valley, Co. Wicklow.” NUI, The Journal of Irish Archaeology, 21 : 85-112, 2012.

2) Dolan, Brian. “Traditional Charcoal Making Experiment.” Leaflet. 2010. charcoal.seandalaiocht.com

3) “Simple Technologies for Charcoal Making.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO Forestry, Paper 41, 1983.

4) “Post-medieval burnt spread and pit.” 2007: AD39 Russagh 2. Database of Irish Excavation Reports.

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions and suggestions for further research are welcome. No selling, no trolling, and back up any critique with modern scholarly sources. Comments that do not meet these criteria will be discarded.